Explorer

In 1906, in the summer after his senior year at Harvard University, Ober took his first canoe trip in the border lakes region. It was the first of many trips to a wilderness he came to know better perhaps than any other living person outside the native population. For decades as an adult, he would canoe an average of 500 miles a summer.

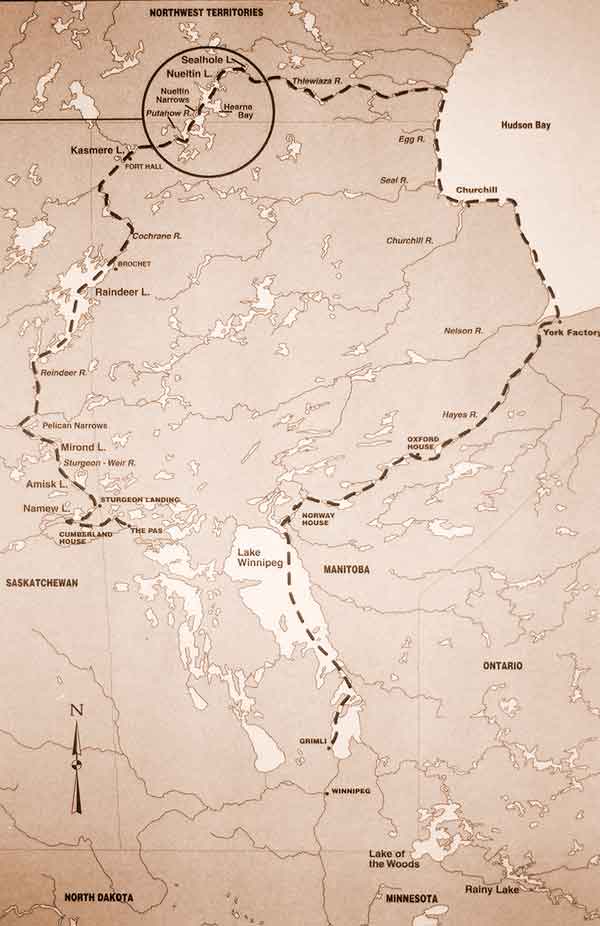

On June 26, 1912, Ober and Billy Magee set off on 2,000 mile, four-month journey to Hudson Bay and back, a journey that was considered a great accomplishment by explorers and canoeists alike. On this trip through the uncharted Canadian Barren Lands, Ober was often the first white man ever seen by the Native Americans in the villages they passed.

June 26–November 5, setting out at the end of the railroad line at Le Pas, Manitoba (west of Lake Winnipeg), Ober and Billy Magee head “toward magnetic north,” exploring an unmapped territory that hasn’t been visited by a white man since Samuel Hearne traveled through the area in 1770. Because of Ober’s aversion to killing animals, they do not plan to hunt for food along the way. As a result, they must pack extra supplies, 700 pounds of equipment in all, which requires them to make five round trips per portage for the first part of their trip. They carry “the three staples of the north, flour, pork, and tea” as well as “such luxuries as evaporated potatoes, raisins, cornmeal, oatmeal, cocoa, sugar, beans, rice, and dried fruit.” It is a considerable undertaking for both men, but perhaps especially for Ober, who stands five feet six inches and weighs less than 140 pounds.

Beginning on the Saskatchewan River, they paddle north to the 170-mile-long Reindeer Lake. There, without a guide, they thread their way through a “labyrinth of islands, long bays, headlands, and points,” never completely certain of their location. The first 500 miles of their trip is against the current. For more than a month they see caribou daily, sometimes in great numbers. Disoriented in the nearly treeless landscape and lost in the deep bays and countless islands of Nueltin Lake (also called Sleeping Island Lake), they spend days searching for the continuation of the Thlewiaza River, which is their passage east to Hudson Bay.

Exhausted, discouraged, and worried that they might fail to reach Hudson Bay before the onset of the sub-Arctic winter, on August 21 they climb to the top of a 600-foot-high island esker (a narrow ridge formed by a glacial stream), a place they think later travelers would be likely to visit. There, Ober leaves a note in a dried milk can, secured in a cairn of rocks, with what he fears may be his last words to his mother. Ober calls the esker “Hawkes Summit” in honor of Arthur Hawkes, the name by which it is known today.

Finally the two explorers, exhausted and occasionally hallucinating, find the entrance to the Thlewiaza River, where they see a seal. Hindered by ice in the mornings and tormented by black flies in the afternoons, they make their way down its shallow, rubble-strewn waters and struggle with their gear along the rocky portages.

September 12, weeks later than planned, the two explorers finally reach Hudson Bay, where they are greeted by an Inuit in a kayak. The Indian, named Bight, is the first other human being they have seen in thirty-four days. He shows them warm hospitality and gives them, with their canoe, a lift in his whale-boat to Churchill for a fee. Two photographs—one of Bight’s ten-year-old son with a pipe in his mouth assuming “a shrewd, wizened appearance,” and another taken at Bight’s family camp on Egg Island of an old woman bent beneath a load of wood and “hobbling along with two sticks”—are extraordinary. They are perhaps the most powerful, haunting, and unforgettable of all Ober’s photographs.

Stuffing their shoes and surrounding their legs with dry wild hay to keep from freezing, they paddle 300 miles from Churchill south to York Factory, following the west shoreline of Hudson Bay. The slope of the shore is so gradual and the water at low tide so shallow that they are forced to paddle from two to twelve miles from land, where they are at risk of being caught by storms with no escape.

Against the advice of the post manager at York Factory, they continue their journey south, traveling against the swift current of the Hayes River toward Lake Winnipeg. Fighting freezing temperatures and frequent snow, they paddle for their lives, often traveling fourteen hours a day.

When they reach Norway House at the north end of Lake Winnipeg, they are told that the last south-bound steamer of the season had departed just two days earlier, and they realize they must paddle another 260 miles to Gimli, where they can catch a train home. It takes them eighteen days, six of which they are snow- and wind-bound, before they finally reach their destination.

Throughout the trip Ober keeps meticulous notes with the intention of writing a book-length narrative. Until nearly the end of his life, he continues to hope that some day he will get around to the task, but he never does. Nevertheless, the extraordinary 2,000-mile, four-month journey makes Ober and Billy legendary figures among outdoors people, and Ober later refers to the trip as the single most powerful experience of his life.

Conservationist

During the lean years of 1931–33, Ober declined to draw his salary from the Quetico-Superior Council because he didn’t want to deplete its meager resources. He once observed, “Common sense tells me to drop the whole struggle, but common sense is a very small part of my whole make-up.”

–Ober, 1933

“It was still a place of rare delight—a region apart from the modern world, where man could enjoy the profusion of nature as completely as in the days of Columbus. There was nothing wilder in the jungles of Brazil or the heart of Africa. It was not a somber forest, but a forest threaded with sparkling waterways, flooded with sunshine and peopled with all its ancient creatures.”

–Ernest Oberholtzer, 1929 American Forests

“We preserve our masterpieces of art. Why not preserve also a few masterpieces of Primitive America?”

–From a statement by Frank Hubachek’s Twin Cities group of conservationists opposing a plan to build a series of dams in the Rainy Lake watershed, 1927

Ober’s 1927 plan to declare the ten-million-acre Quetico-Superior region an International Peace Memorial Forest envisioned “a vast international park, four times as large as Yellowstone and excluding all economic exploitation.”

–Ober

“The truth is that while some attempts have been made to guard and restore a small part of the material resources of the region, scarcely anything has been done until lately even to recognize – much less protect – those far more unique and precious factors involved in the spiritual resources… a policy of disastrous and needless waste has been pursued, resulting in exhaustion of one form of natural wealth after another and in complete blindness to the higher social and cultural uses. Each exploiter in turn has had an eye single to the one resource he coveted and to his own immediate advantage. He never sees the country himself but sends instead his agents, thus running no risk that he will be converted to the public point of view. His “practical” mind views the so-called ‘wild-lifers,’ with ill-disguised scorn. By comparison, the pubic interest, which must always look to the future even more than the present, has been ignorant of its inheritance and infantile in its will to live. Private enterprise has run riot like a bull in a botanical garden. It would look as if we could appreciate our blessings only after we stamp them out. To hesitate or bewail is useless. The responsibility rests ultimately upon the public and upon the public alone.”

–Ernest Oberholtzer,1929 American Forests

“It happens that I was called upon to take charge of this movement [serving as president of the Quetico-Superior Council], which I agreed to do for six months, but that was nearly thirty years ago.”

–Ober

“What was sought through uniform measures in both countries [the U.S. and Canada] was a system of zoning to insure conservation in the use of renewable natural resources and above all preservation for public health and enjoyment of the distinctive wilderness character of the lakes and streams.”

–Ober, 1957

Landscape Architect

In the winter of 1907–08, Ober pursues one year of post-baccalaureate studies in landscape architecture at Harvard under Frederick Law Olmsted, son of the designer of Central Park in New York City. Of this experience, he once commented, “Architectural drawing was dreadful for me, that formal drawing with all those tools. You almost always had to work with an architect in this kind of planning, except for wilderness planning, which was the thing, even then, that appealed to me.”

This training no doubt assisted Ober in his planning and design of the buildings on Mallard Island. Constructed of native materials, the buildings blend harmoniously with their natural surroundings.

Musician

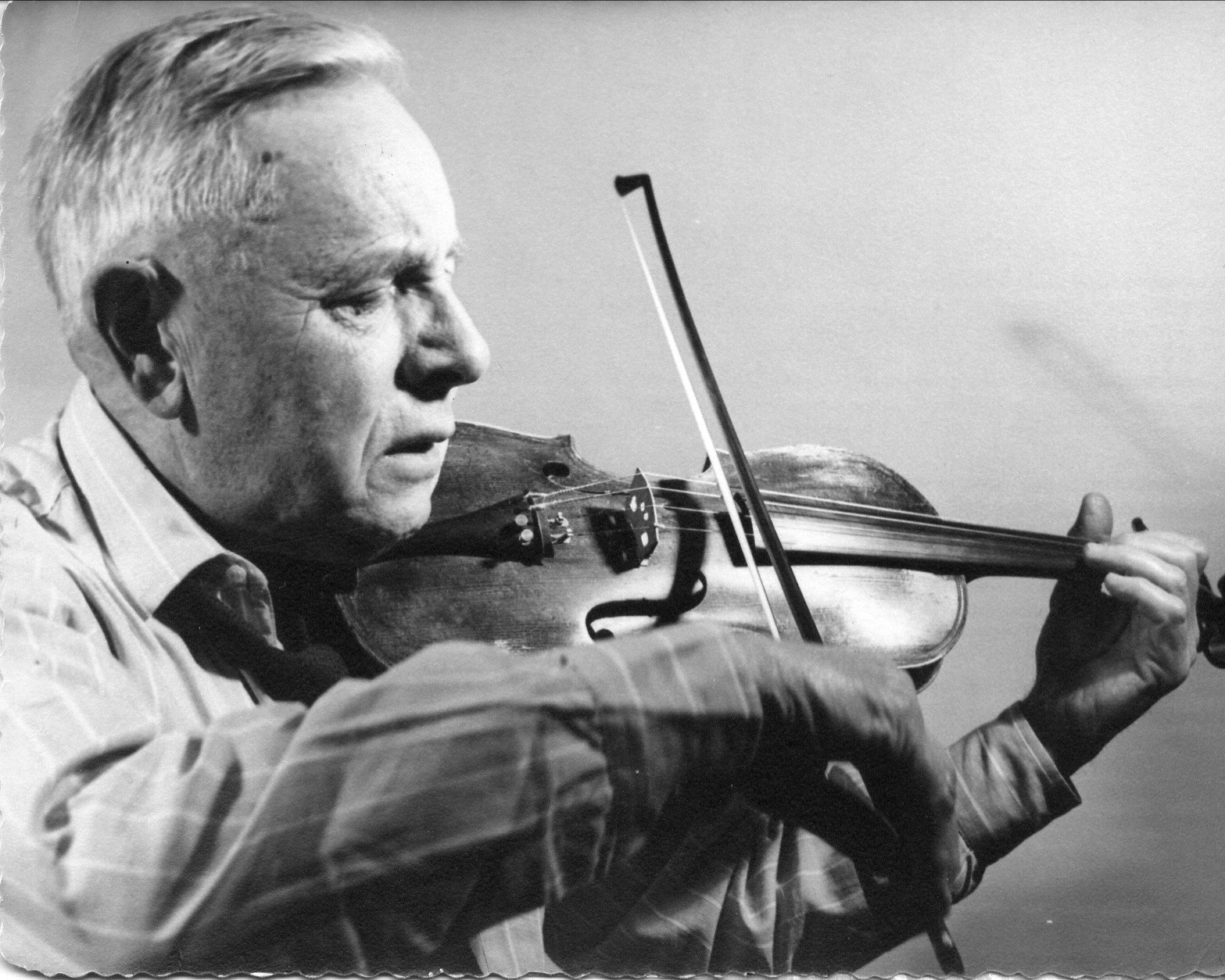

For Ober’s great love of music there were pianos, violins, hundreds of records, and sheet music on Mallard Island.

When Ober was 11 years old, his Grandfather Carl gave him a three-quarter size violin, a gift that led him to begin a lifelong study of the classical violin.

At Harvard University he studied the violin under Boston Symphony concertmaster Willy Hess, and he played in the college orchestra.

Over the years he entertained many guests on Mallard Island, often accompanied by his mother Rosa on the piano, and he sometimes took his violin along on canoe trips.

Photographer

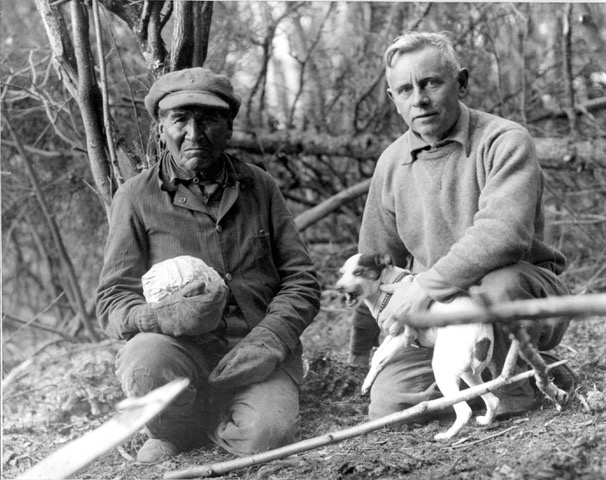

Ober used a large and heavy 3A Graflex camera, about the size and weight of a six-pack, and carried a portable developing box with him. As he described the process, “Every day I developed the pictures I’d taken. I didn’t print them. All I wanted was the negative. I’d string them up from the canoe and they’d be drying as we traveled along.”

Scholar/Reader

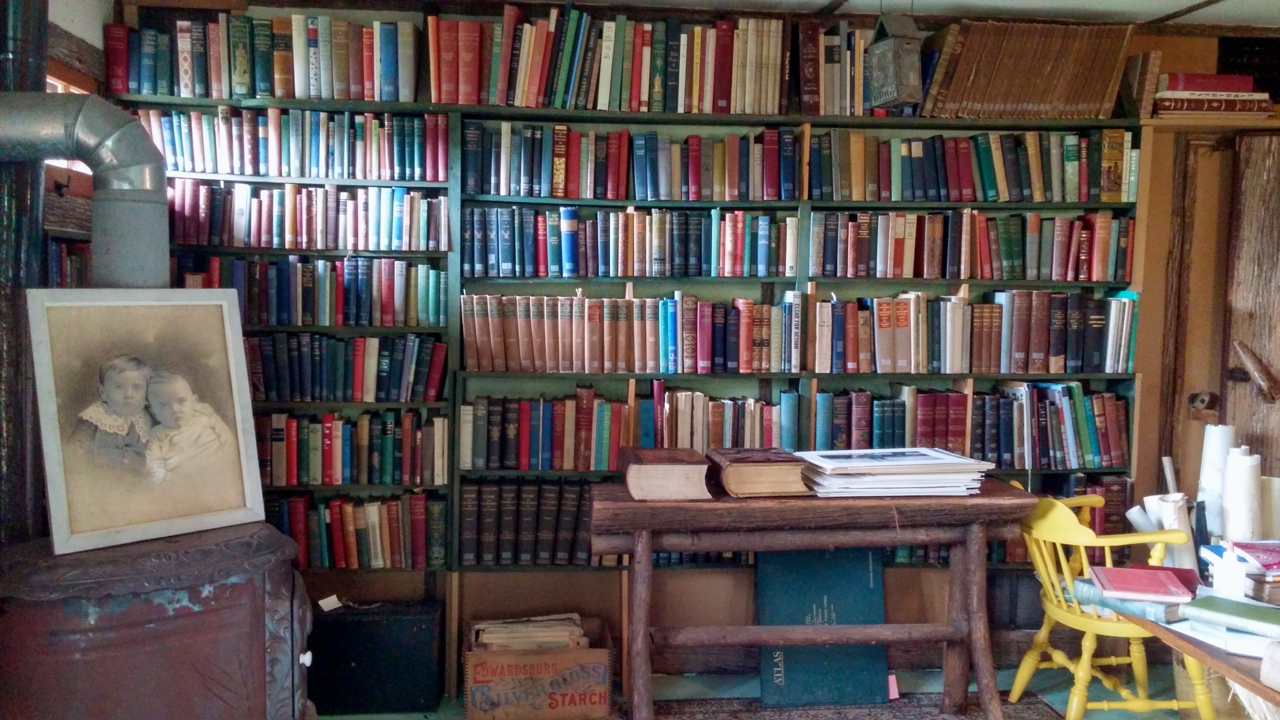

Ober lived for more than 40 years on tiny Mallard Island and turned it into a place of magic, charm, and brilliance. Mallard was Ober’s University, filled with things worth studying, knowing, and loving. He was also a great student of the Indians and collected thousands of books and memorabilia to serve as a foundation for his knowledge.

A great disappointment to Ober was his failure to write: Though a skilled writer who had published a number of stories and articles, Ober never wrote a book about his 1912 canoe trip to Hudson Bay with Billy Magee nor one about Native American culture. To write these books was a life-long ambition.

In Keeper of the Wild: The Life of Ernest Oberholtzer, Joe Paddock describes Ober’s commitment to writing:

“According to all who knew him, he was a truly exceptional communicator, and throughout his life he would write and write well. There would be an endless flow of letters, often delightful; a number of adventure stories written for boys’ magazines in hope of earning badly needed income; and finally many articles in support of wilderness preservation. But, when it came to writing that might distinguish him as a literary figure or to the writing of that book which would have placed him on the shelf that holds so many of American’s other prominent environment figures, something rose in Ober and blocked him, despite the fact that his journals bristle with self-recrimination for not writing such a book.”

In another reference to Ober’s desire to write about his 1912 canoe trip, Paddock writes:

“Until nearly the end of his life, Ober dreamed of writing a book about the (1912) experience, but he seemed never able to find the time and the focused will to do so. In many ways it had turned out to be a spiritual journey, not something to exploit economically. It was a story in which he had played a heroic role, and it seemed that something deep in him blocked his efforts to so celebrate himself. Still, his desire to write of the journey persisted, and in the oral history interviews he often mentioned this subject: . . . ‘I couldn’t just sit down and go into this story. Thoughts of it just shook me. Whenever I thought of it, it was just a landslide, you see.’”