Ernest Carl Oberholtzer

Words of Biography

A few writers, across the years, have tried to put pen to paper in biography of Ernest C. Oberholtzer. In 2001, Joe Paddock published the most known biography for “Ober,” as he was called in the north country, and to this day, KEEPER OF THE WILD is the best place to start when you are trying to understand this multi-faceted and interesting life. (Published by the MN Historical Society Press)

Ted Hall, friend to Ober since Ted’s young age of 12 or 13 years, wrote biographical information in a commentary piece for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, published in September 1983. Ted also published a 21-week series of articles for his own Rainy Lake Chronicle, called “A Clash of Giants,” written by R. Newell Searle. The Chronicle later featured another 4-part series called, “Atisokan: His Rainy Lake.”

Joe Paddock begins his introduction with words that stand the test of time: “We have too few environmental heroes to allow one so important as Ernest Oberholtzer to slip from our collective memory.” Not all call Ober “hero,” yet it is true that he stands with a few strong leaders in our north country who have given their lives to the larger causes– to the care of the Earth, the careful watching of water levels, and the call for federal protection of wild places.

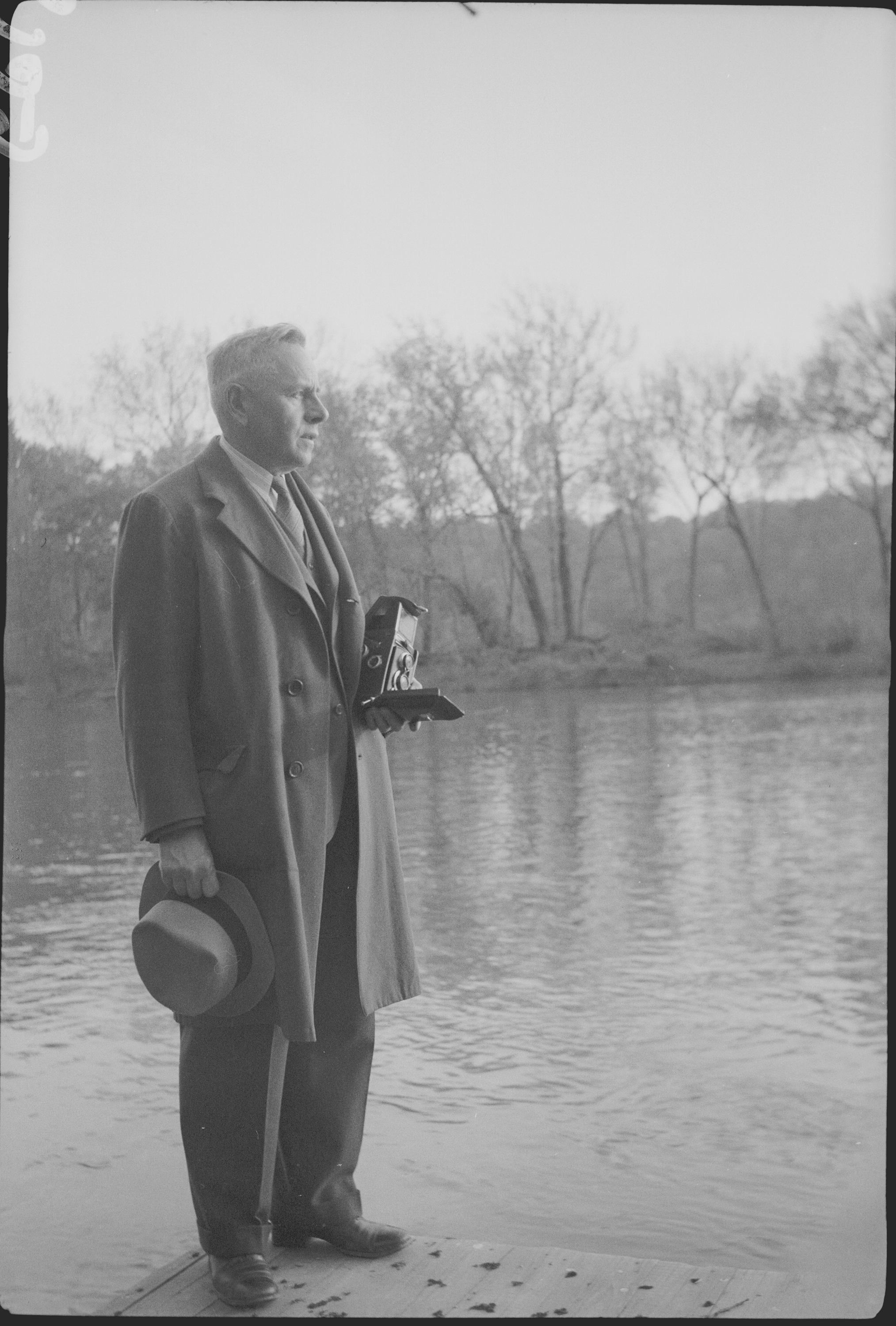

All agree that Ober’s life started in Davenport, Iowa. Most would say that his young life carried more than his share of grief and loss. “Ernest Carl Oberholtzer was born of the marriage of Henry Reist Oberholtzer and Rosa Carl on February 6, 1884.” A ten-pound baby boy would grow up to be a man of small stature, and as Paddock continues, “a man of quick intelligence, warmth, humor and kindness,” a man with a magnetic personality that “drew a complex community of people to gather around him for his presence and to support his goals.”

Ober’s small family would break apart after the death of a younger son and brother, Frank, and later the divorce of Rosa and Henry in 1890. Grief and loss. Ober and Rosa went to live with her parents, and after their fairly early deaths, Ober’s heart was weakened by rheumatic fever. Rosa became a closely devoted mother. Though his doctors once gave him only a year to live, Ernest Carl Oberholtzer would go on to live a long and productive life, dying at the age of 93 in the year 1977. A Harvard education featured boldly in his young story, and he traveled widely including to England and Germany, to the far north of Canada by canoe, and eventually to Rainy Lake.

Ted Hall says more about Ober’s journey north: “Ober came to the Minnesota Ontario boundary waters area at the age of 25 to see for himself the country then being called our last frontier. The year was 1909 and he was fresh out of Harvard…”

“Ober had studied to be a landscape architect, a trade of little promise in a country already landscaped satisfactorily by a passing glacier, and he fell easily into another trade—that of writing about this new frontier that he now considered home… Ober was in his tenth year of borrowed time when he staked out his own little sliver of granite in this granite land. It was called Mallard Island, one of a picturesque group of five islands…” in the border lake called Rainy Lake.

In 1912, an Anishinaabe canoe guide and leader, Billy Magee (or Tay-tah-pah-swe-wi-tang), would accompany Ober on the epic canoe journey of both of their lives, a 2,000 mile trek in the barrenlands of Canada including hundreds of miles of unmapped territory. That journey seemed to secure Ober’s place in the fate of the far north, and his career included decades of support for the Quetico-Superior region as a wilderness area. Ted Hall writes, “Let us simply note that through that long battle (for the Quetico-Superior) Ernest Oberholtzer’s Mallard Island in Rainy Lake was the real headquarters—the touchstone—for the battle, and upon his death, friends steered his island home into the foundation he had set up a dozen years earlier to carry out his quiet work as teacher or friend of the wilderness,” and of the Anishinaabe People. Ober was a photographer, a patron of the arts, a violinist, a reader, a writer, and a collector of books and prints and other fine things rather rare to hold on the Canadian border.

Ober’s friendships were key to his success in the world. He made friends easily and carried them along most of his life. Davenport friends followed him north, and he and his mother (who summered on Rainy Lake for several years) entertained them and shared stories and ideas about life on the lake. His friendships with the local, Rainy Lake Anishinaabe people were crucial to his success on Mallard Island, where they not only visited but helped to build the island and its landscapes. Ober would be cared for and would care for his Anishinaabe friends for his whole life on Rainy Lake, and the purpose he stated for his legacy reflects their deep influence on his world view.

Sigurd Olson, renowned wilderness advocate and writer, spoke at Ernest Oberholtzer’s funeral. “Those who remember Ober see the merry twinkle in his blue eyes, his violin, the ‘Bird House’ he built high above the treetops from which he could look over the water, his gardens growing in soil he had brought from the mainland to the cliffs of his rocky home. If anyone was to describe Ober, it would be as one who loved the wilderness, for he believed a world without wild places was meaningless. He left us a rich heritage of courage, love, and dedication to the dream he carried in his heart until his passing. A man of many facets, he was a gentleman of the old school who loved nature with a passion and gave of himself to others for what he believed.”

Joe Paddock adds his words of eulogy, “It seems that when, early in the 20th Century, the Rainy Lake Anishinaabe People gave Ober the name of Atisokan, meaning legend or teller of legends, this naming contained a touch of humor, but it had nevertheless hit the mark. By the time of his death, Ober and his story had grown to fulfill the dimensions implied by his Ojibwe name.”

Compiled by Beth E. Waterhouse, Executive Director of the Ernest C. Oberholtzer Foundation at the time of this writing, August 2018.