Important People in Ernest Oberholtzer’s life (alphabetized)

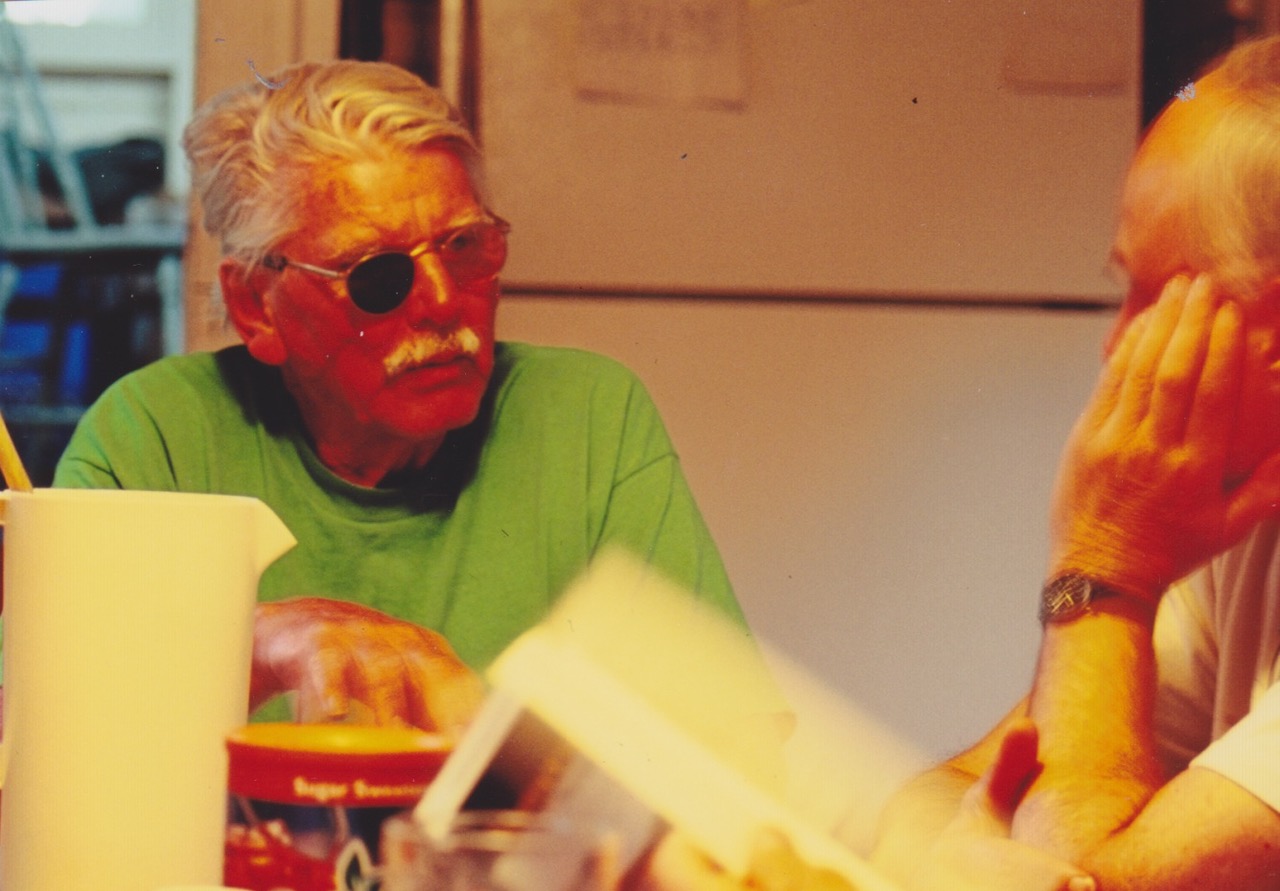

Ray Anderson

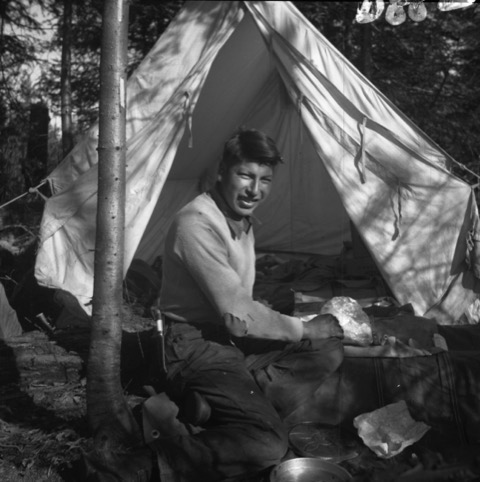

In an August 2008 interview, Ray Anderson described how he had heard about Ernest Oberholtzer most of his young life, and later met him when he added labor to the building of the “Big House,” or what Ober fondly called “Old Man River House” built from 1938-1941. Ray helped with the hard scrabble work of “picking rocks” or scrounging for stone and rock for the steps, foundation, and lower walls of the Big House. He was 16 years old when he met Ober working with Pete Johnson, friend of Ober’s builder, Emil Johnson.

Ray Anderson was soon taken into service for his country (World War II) and he returned needing the solace of a camping and canoe trip, taken with Ober. This is from Ray’s writing about that trip:

“We spoke of many things on this trip toward the tail-end of World War II, a trip which was mostly to observe and photograph and report on the J.A. Mathiew log drive bringing logs down from the Quetico… One thought that influenced all of my thinking since that time was Ober saying, ‘We are of no more importance than a blade of grass.’ The we of which he spoke was not just me and him but all of the race of mankind, which is a part of Nature, sharing the planet with all living things.”

Ray describes their friendship across the years as a strong one, and anyone reading the journals or correspondence of Oberholtzer in the 1940s and 1950s heard mention of “Ray” helping with this or that. By the early 1950s, Ray was even the one to help Ober get to the hospital when his health was poor, and he was one to help Ober move into the Frigate Friday house when it was moored on shore at Bancroft Bay. A shared interest in photography also tied them together.

Ray got a camera for graduation, and the next year his parents helped him create a dark room. For a while he had a studio in International Falls, but since he had lost an eye in the war, when he got a cataract in the other (good) eye, he had to quit with the photography business. After Ober passed away in 1977, Ray was sitting with the board of directors in Ober’s drum room. He noticed a box of negatives there, all in disorder. He brought them home and spent years organizing the images and the negatives by topic. Ray created a 1983 listing of all of Ober’s personal photography by topic or subject, which is the base of our organizing of the photo database to this day.

After Ober knew Ray Anderson, he no longer developed his own images but used the services of his friend. Thus it is likely that no one knew Ober’s photography better than Ray Anderson. In the 1970s, Ray also made prints from all of Ober’s negatives and made duplicate negatives of many of the old images. And, says Jean Sanford Replinger (program founder for Mallard Island), “Ray did all this with no more recompense than to stay one winter in Winter House where he started this work.” Ray served on Jean’s Advisory Committee and he was later named an “Honorary Board Member” for the Oberholtzer Foundation.

Ray Anderson wrote this in a June 18, 1977, letter to Ted Hall: “Your note of Ober’s death brought a sadness. Not a great sadness, because Ober was ready for the big trip and had been for some time. I knew that he would die with dignity and it is comforting to know that the mists cleared away for the start of his last voyage, if only for a short time.” Ray Anderson himself, good friend to both the man Oberholtzer and the organization in his name, died in the fall of 2008.

Frances Andrews

Frances Elizabeth Andrews (1884 to 1961) was an environmentalist and daughter of a Minneapolis grain merchant. The Andrews family was struck by tragedy when Mary Hunt Andrews died in 1912 and Frances, unmarried, took on the role as her father’s hostess. Four years later, their brother and son, William Andrews, died in California. Frances (then 32) and Arthur (then 62) were devastated. When Frances met Ernest Oberholtzer, they were both in their early forties, and we note the first family correspondence in 1928.

Joe Paddock, Oberholtzer’s biographer in Keeper of the Wild, describes Frances’ relationship with Ober as a “deep and loving friendship,” and he points out that “their tie was a platonic one, and Ober was careful it be seen as such.” We know that their almost daily correspondence in the later years is a true window into the lifestyle that each was living at the time. Frances Andrews’ papers are co-located with the Oberholtzer collection at the Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN. Frances’ estate also helped to establish the Hunt Hill Audobon Sanctuary in Sarona, Wisconsin.

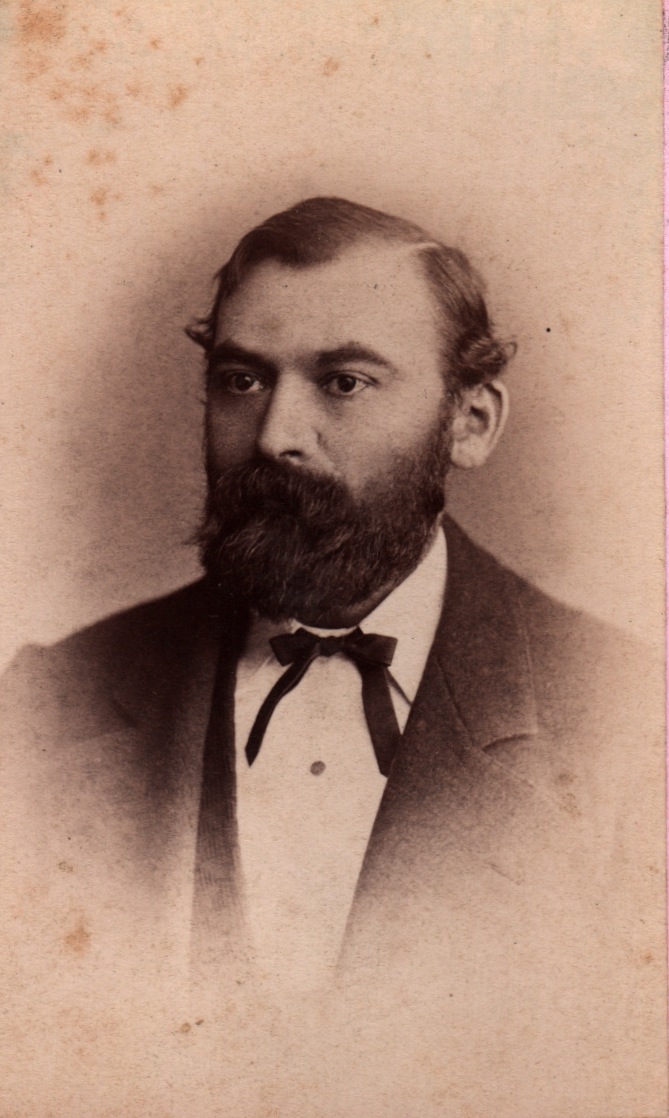

Edward Wellington Backus

“In 1925, Ober learned of a plan by Edward Wellington Backus, a powerful industrialist who happened to be Ober’s neighbor on Rainy Lake. Backus’s plan was to build a series of dams along the Minnesota-Ontario border that would turn the boundary waters into a vast storage basin for industrial water power. For the next five years, Ober led a campaign to defeat the plan and to win greater protection for an area he considered one of the most beautiful regions on earth.”

Lumber baron and industrialist Edward Wellington Backus financed construction of the dam at Koochiching—now International Falls—to provide waterpower for his Minnesota and Ontario Power Company (later called the Minnesota and Ontario Paper Company). The dam, completed in 1909, was to be the first in a series of dams creating storage basins for waterpower that would affect parts of what is now the Superior National Forest, Voyageurs National Park, Quetico Provincial Park, and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. When Ober learned of the plan in 1925, Backus’s paper mills were the second largest in the world in terms of total production. Ober led the successful five-year fight against the plan, which was finally defeated with the passage of Shipstead-Newton-Nolan Act in 1930.

In 1931, after years of preoccupation with the conflict over his waterpower plan and after major investments to expand his paper mills during a period of economic downturn, Backus’s business went into receivership. In October 29, 1934, Edward Wellington Backus, the last of the great lumber barons, died at the age of 73 of a heart attack in his rooms at the Vanderbilt Hotel in New York City.

Of his death Ober wrote, “So tragically alone at the end . . . without the comfort of real friends. I know the sadness of it . . . and what great qualities he had. His lonely death makes his life, with all its triumphs, seem pathetically hollow. I will miss E. W. One cannot be in harness with a team mate for so long without missing him.”

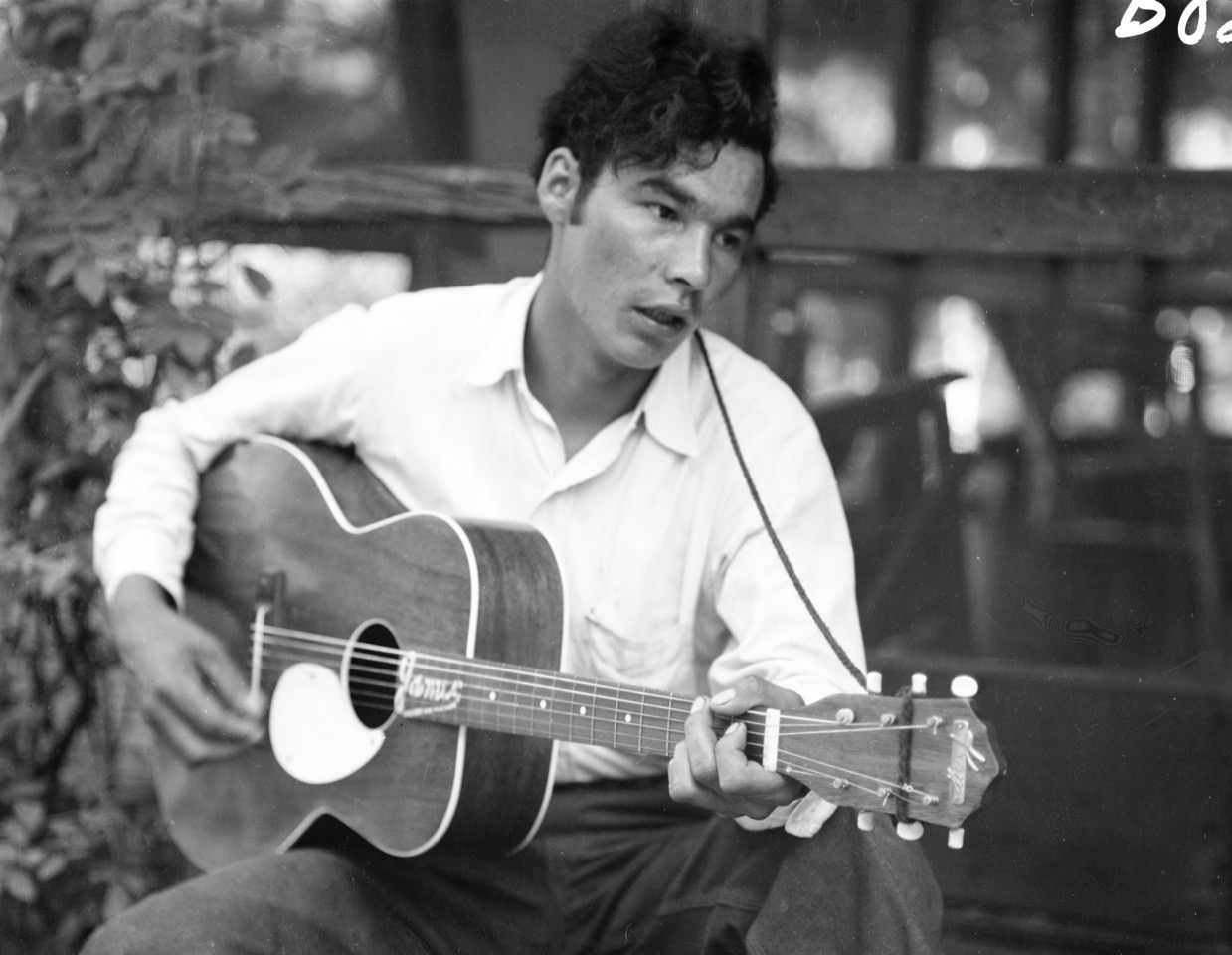

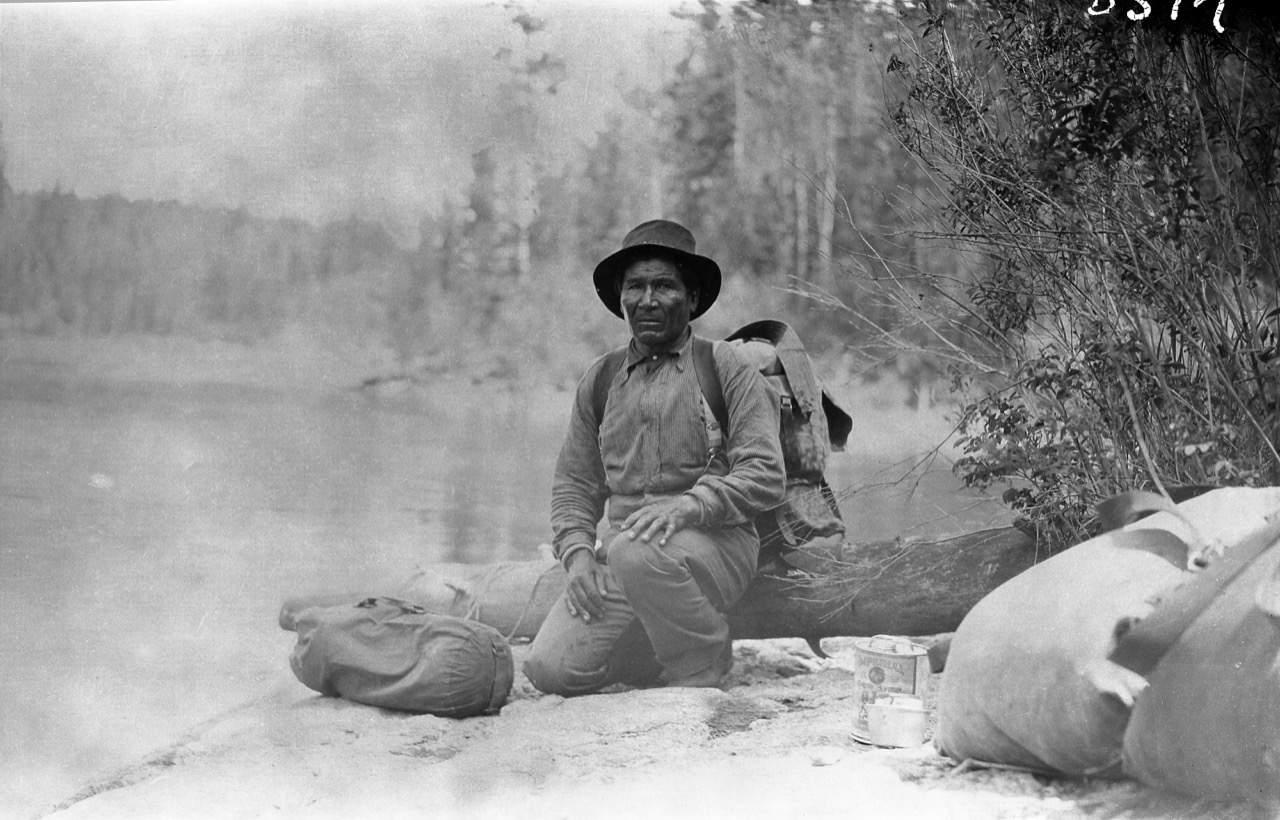

Jim Banks: It was His Country

By Harvey Broome

Ober managed to get Jim Banks to guide a short canoe trip in September 1956. The group included leaders and families involved with the Wilderness Society. In an article written that year by Harvey Broome, President of the Wilderness Society for a time, Jim Banks appears as an important character. Harvey expresses deep respect for his skills and his knowledge of the northland. Here are selected excerpts shared in memory of Jim:

“Jim Banks was reserved. He husbanded his words. His face was similar to that of some Mexican Indians I have seen. It was slim and dark, with flashing black eyes. There was no flaunting of his strength or his competence. He launched the first canoe and packed it, and I joined him as bow paddler. Enroute he spotted a mink, used one word to call it to my attention, and then twisted and turned the canoe until the creature was almost under me—looking up with terror in its eyes before it dived.

“I did not know how far we had to go. I felt awkward; and self-consciously felt I was being weighed in the balances of the north country. Perhaps I was. I asked Jim to criticize my paddling. ‘You do all right,’ he said.

“<Later, on land> another storm was coming. Jim said, ‘It will rain again.’ And then I felt at home. How many times have I put up a tent against the rain in the Smokies! I unrolled our mountain tent, showed Jim how to fit the stakes together, and before the others arrived we had our tent up…

“The next morning we readied our canoes for a trip up Crackshot, into Whitewater, and perhaps on to Eagle Lake.

“When he slid his canoe into the lake, Ober said to Jim, ‘Who’s going with you?’ Jim said, ‘I take Harvey.’ And my heart jumped that those restless timeless eyes had seen me. What a curious thing that I should secretly glory in his favor…

“I should like to think that some of my pleasure came from recognition of the oneness of this Indian boy with his environment. Perhaps, though changed as it is, he felt more at ease here, more at home, than any city people ever feel under the demands and tubs and stresses of complex urban life.

“He of course brushed white civilization on every hand. He spoke our tongue. Back on Rainy Lake he operated an outboard motor. He was paid in money. He wore white people’s clothing, and when his shoes got wet, he even donned Bean boots.

“But this was his country. He was too young to have known it at its best except by the stories of his elders, but, wrecked and impoverished as it is, he felt at home.

Here was simplicity, here the exaltation and resultant weariness of hard work. Here people drew together around the cook fire. Here everyone worked to a common purpose. Indian life had been like that, and he perhaps enjoyed our stumbling and fleeting imitation.

“Going up the lake, always cut corners. He would hold close to every point—always safely out. He said once in one of the few remarks he volunteered, ‘I like to paddle close to the shore.’ Here were the trim spruces, the ragged cedars, careless firs and bunchy pine. Here the multicolored lichens and mosses, the flush of the blueberry bushes, the flash of the eagles. Here was the detail—the open book—which Jim loved, and which he read with a discernment lost to us.”

= = =

James Banks, O-Zhaa-Wish-Gobii-Taan, died September 20, 2012. Jim worked for and with Oberholtzer on Mallard Island for several summers during the 1950s. He and Frances Andrews were also very good friends. Nancy Jones (Ogimaawigwanebiik) is his sister. Jim taught several Canadian gardeners the details of Mallard’s historical garden spaces. His energy remains part of the island.

C. Robert Binger

C. Robert Binger was born September 11, 1918 and died on August 14, 2012 at the age of 93. Like Oberholtzer, Binger was a member of the “Explorers’ Club.” For Bob, this was in recognition of five sled expeditions into the Canadian Arctic, meeting nomadic Inuit peoples from 1965 to 1970. Bob Binger also served in World War II and participated in the landing at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

A decade ago, a good friend of the Foundation and sometimes scribe for the Board of Directors, Barb Breckenridge, requested details about the connection between Bob Binger and Ernest Oberholtzer. Bob recalled three stories about Ober, and here are excerpts from Bob’s letter to Barb written in 2001:

“We lived in International Falls for eleven years (1947 – 1968). I worked for the Minnesota and Ontario Paper Co. in Minnesota and in Canada. I became acquainted early on with Ober and often was at his house (Miss Andrews’) where he played his violin for us.

”My first story took place on Frigate Friday... Ted Hall and I were visiting Ober one evening on the Frigate Friday and Ober verbally described his 1912 canoe trip with Billy to the Arctic. He showed his glass slides, some of which he had sent to Japan to be hand colored… We had kerosene lanterns for light, which helped to enliven Ober’s story. He described the note he left in a baking powder biscuit [sic] can for his mother, which he left in a stone cairn on a high promontory on Nueltin Lake. This information later turned up on a visit my family and I made to Churchill on the train at a subsequent date.

”The second story has to do with a trip my son and I took Ober on to an old gold mining camp called Pickle-Crow(?) north, far north, of Red Lake Ontario in northwestern Ontario. We drove this long distance, often on a single lane road or trail. During this drive we crossed the Albany River at the outlet of Lake St. Joseph. This was the site of an old Hudson Bay Post, now abandoned. At this location we saw a group of teepees and Indians back in the woods tanning moose hides. Ober got very excited and ran over to talk with these people, advising them of his nick-name, Atisokan (storyteller). We had a wonderful visit and I had an elderly woman measure my feet for beaded moccasins. She would not take any money, payment to be made when I received them. I received them in about 3 months time.

”A third story, and the last one, involved an accidental meeting with Ober during our visit by train to Churchill. Ober happened to be there, I believe, on his return from a trip back to Nueltin Lake with Bob Hilke… Ober had gone on to Churchill to locate a white trapper named Windy Smith who had discovered the note Ober had left there many years before, advising his mother not to worry if they didn’t get back before winter set in. I was with Ober when we met Windy Smith and learned about his discovering the cairn and the note.

”Ober often visited friends in Minneapolis in the fall. The Winstons, I believe, and on one of such occasions Ober came here and had supper with my family and we all listened entranced by Ober’s descriptions of some of his experiences.”

In recent years, Bob Binger often met with Bob Hilke when Hilke was in town and traveled out to White Bear Lake. Our board president, Jim Fitzpatrick, also knew Bob and the Binger family, and we end this tribute with a quote from Jim:

“I went to Bob’s memorial service (Sept 8, 2012) representing both the Fitzpatrick Clan and the Oberholtzer Foundation Board. I recognized my classmate, Tom Binger. Bob was quite a person. My dad knew them well. In fact on our canoe trip down the Turtle River into Rainy Lake in 1959 he worked out the use of two outboard motors and gas to get our canoes from Redgut Bay to Fort Francis. We got them from the paper company yacht that was stationed in Redgut Bay. And Mr. Binger was there.”

Ernest and Sarah Marckley Carl

Harry “Pinay” Boshkaykin

Harry “Pinay” Boshkaykin first canoed with Ober in 1945 when he was about 8 years old. Ober had hired Pinay’s older half-brother, Bob Namaypok, a talented visual artist, to guide him on that trip, and Pinay tagged along.

After his half-brother died from tuberculosis at a young age, Pinay regularly accompanied Ober on his canoe trips, which often lasted more than a month.

As Ober had done with his earlier travel companion Billy Magee, he and Pinay often went out in search of moose. As reported by Joe Paddock, Pinay later described one of those trips:

“Ober never . . . had a gun. All he has are hatchets, little hatchets. I’d be scared. Sometimes a moose can run over you. But never done to us at all. If you talk bad things about animals, they hear you, what you say about them, and that’s why they come after you.

“When we see a moose, Oberholtzer tried to say something with the moose sounds. I was scared. ‘Don’t say that,’ I say. He made sounds like a moose. The moose is looking at us, big, you know, in front of the canoe. I paddled behind. A bull moose come over close. Yeah, he learned that, he learned to make the sounds of a moose. The moose was looking at us. Then he came toward us, about ten feet away. Oh, boy, Oberholtzer really laughing. He’s joking and laughing. He waited for [another moose, and for] another picture. He laughs. He say, ‘That will make a nice picture. That was nice of you.’ He say to the moose, yah. I think he does talk to animals, try to say something. Oh, yes, I think so.”

Tom Burke

Harry French

Ernest Oberholtzer and Harry French grew up together in Davenport, Iowa, and remained friends throughout their lives. In 1910, when Ober was paddling the Rainy Lake watershed with Billy Magee and had been interrupted for other reasons, he happened upon a telegram from Harry, who had just graduated (also from Harvard). As a reward, Harry’s father had given him a 3-month trip to Europe with one friend. Harry chose Ober to accompany him. (Paddock, “Travel and Work in Europe” from Keeper of the Wild, pages 66-68.) This adventure added a great chapter to Ober’s life story. The two traveled throughout England, including London; to France, including Paris, and to Austria, Hungary, Switzerland and Germany. Ober ended up staying on in England following Harry’s return to America, renting a room in London.

In about the 19-teens, when Oberholtzer was establishing himself up on Rainy Lake (working for Hapgood and other projects) he attracted many Davenport friends to the north country. One was Major Horace Roberts, another was Harry French. And it so happened that Harry French fell in love with Virginia Roberts (daughter of Horace) and the two established themselves up on Rainy Lake at a place called “Green Isle” or French’s Island. Over the years, as their friendship continued, Harry was often willing to loan money to Oberholtzer, who always worried about the debts and intended to pay them in full. It appeared, however, that at the untimely 1948 death of his friend, Harry French, Ober still owed him $9,000— and Harry’s will promptly forgave that debt in full.

Harry and Virginia (Roberts) French had two daughters, Alice Virginia (soon known as Algene) and Audrey, who also grew up both in their home in Davenport and in their more adventurous summer lives up on Rainy Lake. Audrey suffered an early death due, in part, to a boating accident and in part due to her childhood condition of asthma. Algene French married William Primrose (violist), always maintaining her friendship with Ober and her love of his home island, Mallard.

Charlie Friday (Giiwewosaadang)

Charlie Friday, whose Ojibwe name was Giiwewosaadang, taught Ernest Oberholtzer much about Indian people and their way of life. Charlie’s mother was from Nett Lake. She was the daughter of Chief Ma-tchiss-Kunk.

Charlie often worked on Mallard Island and did some of the masonry work there; notably the chimney in Cedarbark is his. He also kept in touch with Ober through Ed Bliss at Bliss’s store in Mine Centre, Ontario. During the last years of Billy Magee’s life, Charlie provided Ed Bliss (and through him, Ober) with reports on Billy’s condition and needs.

In 1956/57, when Ober moved the Frigate Friday houseboat up onto land to become a small house on Bancroft Bay, Charlie Friday built the fireplace there. He was proud of his stone work and said that he’d like his spirit to reside in that chimney someday. Decades later, Ted Hall wrote this in a July 1979 issue of the Rainy Lake Chronicle:

The graceful stone chimney he built… was ten years old when by an unexpected mix of fate and gasoline and fire Charlie Friday suddenly was made eligible to fulfill his vow to dwell someday as a spirit in that chimney. No one who knew Charlie Friday… doubted thereafter that Charlie Friday was in residence in that delicately-tapered chimney.

After the houseboat was moved back onto water, the land was sold, and Ted Hall heard that the chimney was to be torn down. Ted asked the Indian friends if spirits could be moved, explaining Charlie’s and the Foundation’s desire to fulfill his wish by installing his spirit in the fireplace in the Big House on Mallard. At that time, Joe Friday, Charlie’s brother, went with Jim Boshkaykin to the place and picked up one of the round stones there. Later he and several others (Billy Blackwell, perhaps Alan Snowball…) with several Foundation Board members present, completed a solemn ceremony and set Charlie’s stone in a spot on the lower left hearth of Ober’s fireplace in the Big House on Mallard Island. Someone said that it must never be moved again.

Charlie Friday was the father of at least two children: Buddy and Rose. Pictures in Ober’s files later identify three daughters of Buddy. In fact, three of Buddy Friday’s daughters (Charlie’s grand-daughters) visited Mallard Island this July: Dorothy, Patricia, and Bernadette. Another grandson well known to us, Alan Snowball, was the oldest child of Rose Friday and George Snowball. In a 1996 Mallard Newsletter, Jean Replinger said this about Alan: “We were privileged to have Alan spend some time on the island each of the last ten summers. He generously shared his love of the outdoors, his culture, and his family with us and connected the generations who have known and loved the islands.” Alan died in April of 1996.

Dr. Mary Ghostley

Ted Hall

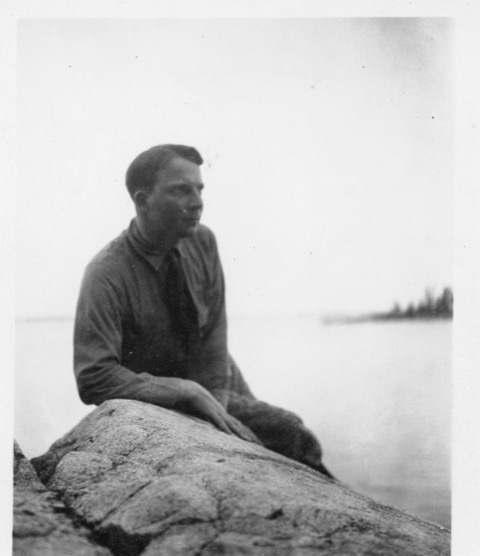

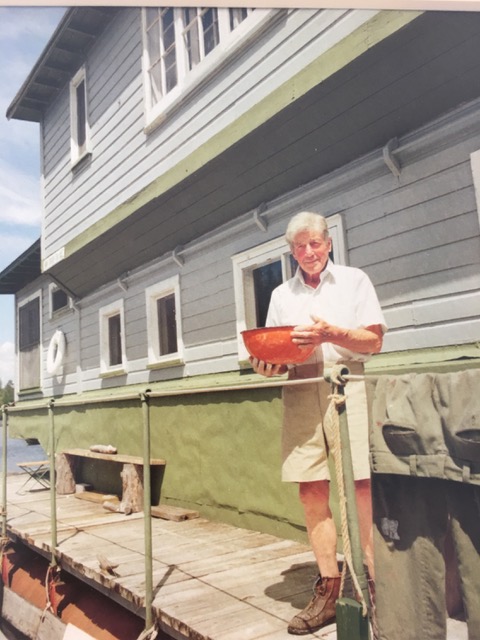

Any who knew Ober after the middle of his life probably also knew Edward (Ted) Hall. Ted was born in 1921 and died in September 2003. He first met Ernest Oberholtzer when Ober traveled to Frontenac, MN, to visit Ted’s father. Soon Ted (37 years Ober’s junior) was attracted to Ober’s ideas as well as to the rocky (grass-free) islands of Rainy Lake. By the late 1920s, he began spending the majority of many summers canoeing or working/living up on Rainy. By the end of Ted’s life, he was again a summer fixture on Rainy Lake, coming and going from his “Frigate Friday” houseboat moored on Gull Island.

Ted Hall was “an honest, tenacious and gifted reporter and writer,” declared Diane Rose, remembering him in the Wilderness News spring 2004 issue. She reported, and son, Thomas Hall later clarified that Ted worked on a series of New Jersey newspapers, covering stories such as the Newark race riots in 1967. Reporting on labor and politics in New Jersey meant covering the mob. The story that got Ted Hall fired from The Herald News implicated a Patterson, NJ politician and the police department in suppressing evidence in a murder trial. Ted then turned down job offers from many major newspapers before going to work at TIME magazine as the New York bureau chief.

By the time Ted Hall was 53, he’d grown weary of what he called corporate journalism. Taking stock of his life, Ted realized that the two things he’d always wanted were to have his own newspaper and to live on Rainy Lake. He bought a Maine lobster boat, “Claire,” in Cohasset, MA, and, with his son, Thomas, aboard part of the time as first mate, Ted piloted her down the east coast to New York, up the Hudson River to Albany, west on the Erie Canal, and across the Great Lakes— some 2,000 miles through rivers, channels, and the Great Lakes to the port of Duluth where he then trucked the boat over to Rainy Lake. [3]

To complete his vision, Ted Hall cashed in his pension from TIMEmagazine to create the Rainy Lake Chronicle, a weekly paper read by all from “Rainy Lakers to big-city people who longed for a taste of the simple life of a village.” [1] The Chronicle was published each week from 1973 to 1982.

After Ernest Oberholtzer’s death in June 1977, Ted Hall dedicated a fair percentage of the column space in the Rainy Lake Chronicle to stories about Ober’s life up on Rainy and Oberholtzer’s decades of work in the world of wilderness preservation. Ted moved Ober’s Frigate Friday back onto water and began to spend most of each summer in it, which put him in close proximity to then-empty Mallard Island and its several 1930s structures. By the time Ober’s named heirs were deciding what to do with the island and its archives, Ted Hall was forming the Board of Directors. The Oberholtzer Foundation existed only on paper at the time of Ober’s death. Ted and others (the Monahan family, etc.) were adamant that the islands be used in common, and in the years following Oberholtzer’s death, Ted Hall plus Gene and George Monahan became key figures in a legal battle to prevent the sale of Mallard Island and to activate the Oberholtzer Foundation. [2] It was Ted’s vision to preserve Ober’s islands intact and to design the foundation’s programs to incorporate them

as the locus of its work. One of Ober’s eighteen heirs, Ted donated his shares of the estate to the Foundation and persuaded enough others to do the same to convey the islands to the Foundation. It was through the generosity of these heirs, and through Charlie Kelly’s deft negotiations with the multitude of separate persons and interests involved that the Oberholtzer Foundation and Ober’s Islands came to be in the form and style we know them today. [3] Jean Sanford Replinger of Marshall, Minnesota, must also be mentioned here as one who designed the first Mallard Island summer programs.

Somewhere in the mid-1980s, Ted and his second wife, Rosalie (Rody), took a second outlandish boat trip in the Claire, this time from St. Paul all the way down the Mississippi River almost to New Orleans. The big river’s debris and sandbars took a toll on the lobster boat, however, and by the time they reached New Orleans it seemed better to donate it to the Sea Scouts than pay to have it trucked back North.

Another significant boat, a scaled-down Danish trawler called The Teahouse of The August Moon, was later Ted Hall’s flagship up on Rainy—you could hear its distinctive one-cylinder thump coming from a mile away. Ted was a good neighbor to those living nearby on the lake. Sometimes he would begin his day by baking a few loaves of bread, and in the afternoon he’d deliver warm bread to his friends on Mallard or Fawn or Jackfish Islands. “Ted bread,” baked in coffee cans, was distinctively round and decidedly delicious. (Recipe available.)

Ted and Rody (Heffelfinger) Hall bought Gull Island while they were married, and, when they divorced, Ted signed over his interest in it to Rody so that she could get the tax benefit from giving it to the Foundation. [3] This triple-win agreement gave Ted a life residency on Gull, and thus, in late 2003, the Foundation acquired Gull Island as one of four in its small archipelago.

Beyond his warm bread and the rhythmic thrum of his trawler, Ted is most often remembered for his uncommon skill with words. No one can write a sentence like Ted Hall, commonly a long thought but so carefully crafted that the sentence bends and flows and breaks into new light and deeper meaning. Here’s a sample selection, to end this piece with a small taste of Ted Hall’s thoughts about Ober. Taken from a collection of his columns in the Chronicle called “Drumbeat,” Ted wrote this thought near the week of Ernest Oberholtzer’s death:

|

We are asked does it make us sad to visit that little island of long-ago golden summers—summers of music and rain and sunshine and good conversation. The question is asked in a garden gone to tall grass in the shadow of fragile buildings that have grown old with the man who built them and shared them generously during the half century the island was his home and his touchstone… It was a glorious instant and it made a spark that glows into the instant that followed… This little island may be the pivot point where man turned to make peace with his planet. Our answer to the question is, we can’t be sad about that.

|

William Hapgood

William Hapgood was a fellow Harvard alum and a member of a wealthy and influential eastern family. Hapgood had interests up on Rainy Lake and began to own much property, including many islands in the region of and including the Review Islands (Mallard is one of five.) Hapgood went on to manage the Columbia Conserve Company (Indianapolis), a business in fruits and jams. Self-interest or other more philosophical interests led William Hapgood to imagine a sustainability project on Deer Island (now Grassy Island) and to hire Ernest Oberholtzer to manage that project from 1917 to 1922. Upon the financial default of that venture, Hapgood owed Oberholtzer back wages and chose to pay him with the gift of Mallard Island (title later transferred and a small fund paid to the county for legal ownership.). By the spring of 1950, Ober was in almost daily correspondence with William Hapgood, then getting on in years, while Ober was helping Frances Andrews purchase Deer Island. This sale went through, and soon thereafter, Ober also purchased Hawk Island and Crow Island from William Hapgood. It was then, again in a letter to Frances, that Ober wrote, ““If I pass on to the next world soon afterwards, someone else can start where I leave off and dream the larger dreams… It seems almost unbelievable that, after living on my little acre and a half for nearly 35 years, I should suddenly expand to ten times that size, but then my unofficial family has long more than justified it. We have been flowing over the edges for a long time.”

Thanks to his friendship with William Hapgood, by the time Ober was in his mid-sixties he was a multiple island-owner on Rainy Lake, owning Crow, Mallard, and Hawk Islands. Frances owned Deer Island until her death in 1961. She willed it to Ober, and Ober ended up donating it to the Camping and Education Foundation.

Meanwhile, a little more about Mr. Hapgood’s idea ~ The Deer Island Project provides an interesting story. Together, Ober and Hapgood (and others, including Hapgood’s children) envisioned making the island into a “sustainability” place for Rainy Lake. They intended to clear land, build cabins, have a general store, raise sheep and goats or other small fur-bearing animals. They promoted the place as “only one night’s trip north of Minneapolis by the Northern Pacific RR.” Ironically, Ober’s mother (Rosa Oberholtzer) chose to come north from her Davenport life in those summers, and she was up to her elbows in this hard work alongside her son. Though they all worked hard, raised 40 sheep, and cleared a lot of land on Deer Island, Hapgood eventually made the management decision to pull the capital from a losing venture, admitting: “I haven’t very much confidence in the outcome…” Although this venture failed, it was most certainly educational. It did provide work for many local people in that decade, and at one point there were even (aborted) plans for the Columbia Conserve Company to build a local canning factory.

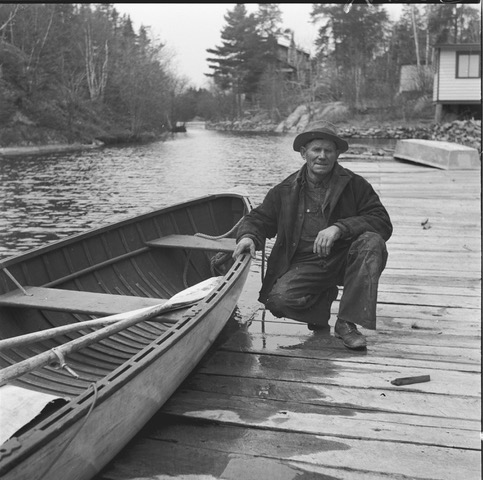

Emil Johnson

In the summer and fall of 1924, according to Joe Paddock, Ober’s biographer, Mr. Bror Dahlberg was trying to get Redcrest (Jackfish Island) built but was having some trouble with a carpenter named Emil Johnson. Under Ober’s supervision, the project did move forward with efficiency, and one of the things that came of this was a friendship and long-time working relationship with master carpenter, Emil Johnson. Emil, when sober, was a genius with wood, especially cedar pole construction. It is said that whatever Ober could imagine, Emil could build. With Emil’s skills, Ober began construction on a series of buildings that utilized native materials and conformed to the natural landscape. We know of Japanese House (the original, early 1920s) and Bird House (1926) and the massive four-story “Old Man River House,” now called Ober’s Big House (1938 to 1941). One might guess that wherever you see original artistry using cedar and cedar-poles on Mallard Island, Emil Johnson might well have had a hand in it. This photo of Emil Johnson was taken in 1945. This dock was in the Hawk / Mallard channel, and you can see the corner of the Kitchen Boat as well as Big House in the background.

Pierrish Jourdain

According to Joe Paddock, “Through the winter [of 1914–15], Ober continued his cultural work with nearby Ojibwe, and by the spring of 1915 he had collected a considerable amount of material.” His principal source of stories and legends during this time was Perrish Jourdain, who was of French and Indian descent and who was nearly 100 years old. It was around this time that the Ojibwe began calling Ober “Atisokan,” which means “legend” or “teller of legends.”

Arthur M. Judy

Reverend Arthur M. Judy was a minister at the Davenport, Iowa, Unitarian Universalist Church, and Ernest Carl Oberholtzer was a member there and learned a great deal from Rev. Judy. The church was just down the street from where Ernest lived with his grandparents (Carl and Sarah) and his mother, Rosa for several years. Judy served that church for 26 years. One thing that may have had a strong influence on Ernest in his growing up years was an entity called “The Outing Club,” formed in the 1891 by Arthur M. Judy and colleagues within the Davenport community. Judy said that one of his primary purposes in founding The Outing Club was to create a place where recreational activities could take place. The club had tennis, biking, bowling, theater, fancy ceremonial dinners, raucous dance parties and more! As one of its “1955 Bowlers,” Ober attended a reunion at The Outing Club in Davenport later in his life.

By 1921, just a year before Reverend Judy’s death, Arthur wrote a letter to Ober (calling him “Ernest,” of course) that demonstrated both his love and his respect and it referred to a possible job opportunity.

“When I read the Antioch Plan, I was captivated by its pioneering spirit, and when I noted that the trustees were searching for men of that spirit to launch the plan, I thought, Ernest is just such a man… Of one thing I am sure, and that is, if you should have the slightest inclination to tie yourself to such a small institution, I would follow my inclination if I were you… When I wrote President Morgan, I said I introduced you without request or recommendation beyond my readiness to back up the character I had given you in my introduction. I would be delighted to counsel with you over the project.”

To have upstanding leaders like Reverend Arthur Judy stand up for Ober and recommend him into the world of various opportunities was certainly “social capital” back in the day, and such friendships were key to Ober’s later success in the realm of wilderness advocacy.

Aldo Leopold

A contemporary of Oberholtzer—just three years younger—Aldo Leopold was also born in Iowa. And like Ober, Leopold pondered over the mighty Mississippi flowing south. Aldo was born in Burlington, Iowa, in January 1887.

Unlike Oberholtzer, Aldo Leopold did not live a long life. He died of a heart attack, trying to put out a grass fire on the prairie of Wisconsin in the spring of 1948 when he was just 61 years old. The world lost a visionary in that particular grass fire.

And just one week before that particular grass fire, Aldo Leopold had heard from Oxford University Press that they had accepted his book. After using the working title, Great Possessions, the book would be published in 1949 as the seminal work, Sand County Almanac. [To date it has sold over two million copies and has been translated into twelve languages. Sand County Almanac helps the reader see with both heart and eye the ecological details of bird and mammal, marsh and forest.]

Aldo Leopold, always the naturalist, studied forestry at Yale University and began his fieldwork near Albuquerque, New Mexico. It was near there, with a forestry crew, that “Leopold and another crew member spotted a wolf and her pups crossing the river. They shot into the pack and then scrambled down the rocks to see what they had done… ‘We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, (wrote Leopold) and have known ever since, that there was something known only to her and to the mountain.’” (1) What some do not realize is that the first part of that story occurred in August of 1909 and the thoughts articulated as a fierce green fire were penned in 1944. Thirty-five years and half a lifetime of ecological education had led to this change of heart about the wolf, the predator, and what it might be to “think like a mountain.”

Leopold served on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin, beginning in what was called Game Management later helping turn that work into the field of Ecology. Aldo Leopold loved canoeing in the Quetico border region, and his work would overlap with Oberholtzer’s when Leopold began speaking and writing about the necessity of wilderness for science, history and adventure. The public debate over wilderness had begun. And in the years between World War I and II, Leopold, along with six others that included Ernest Oberholtzer, was asked by Bob Marshall to help form The Wilderness Society. (1934)

Motivated in part by Henry Ford’s Model T, which took untold numbers of Americans into the heart of Nature, the Wilderness Society came together to “define a new preservationist ideal because of a common feeling that the automobile and road building threatened what was left of wild America.” The group that Bob Marshall pulled together included Harold Anderson (Washington DC accountant), Robert Sterling Yard (National Park Service and hiker), Harvey Broome (Knoxville lawyer and hiker), Benton MacKaye (forester, planner, and organizer of the Appalachian Trail), and Bernard Frank (a watershed expert). “To give the organization a stronger national standing, the group also invited Aldo Leopold and Ernest Oberholtzer to join as founding members.” (2) Marshall called Leopold “the Commanding General of the Wilderness Battle.” (1)

The world of ecology would have greatly benefited from another two decades of Aldo Leopold, much as it did benefit from decades more of the planner and advocate, Ernest Oberholtzer. Leopold left a legacy in The Shack renovated on a sandy farm on the bank of the Wisconsin River near Baraboo. Leopold and his children planted thousands of trees. This land later became a forested island of health in the farmland and marshes surrounding it.

We also know that Aldo Leopold stayed on and worked on Mallard Island alongside Ober and other members of the council of the Wilderness Society. “For four days in June [1947] Zahniser and Ober gathered with Aldo Leopold, Bernard Frank, Bill Zimmerman, Olaus Murie, Robert Griggs, Harvey Broome, and Benton MacKaye to confer about the airplane problem and wilderness conflicts elsewhere… Comfortably situated at ‘the Mallard,’ in Oberholtzer’s delightful three-story wood-frame house, the council… discussed a variety of pressing issues. Leopold explained how the eradication of wolves and other predators had caused deer and elk to proliferate. That, in turn, generated pressure to permit more hunting and build new roads into national forests and other public lands. At his urging, the council adopted a resolution that ‘the unwise depletion of predators is one of the outstanding threats to wilderness preservation.’”(3)

Aldo and Estella Leopold left a lasting legacy in their five children and many grandchildren. “Though Aldo never pressured them to do so, all his children became scientists and conservationists. Starker was a premier wildlife ecologist (he died in 1983). Luna (who died in 2006) is renowned for his pioneering work in river hydrology. Nina and her second husband, Charles Bradley, worked on prairie restoration at the Shack property (until her death in 2011 at 93). Carl was a plant physiologist, researching seed variability (he died in 2009), and Estella, Jr, is a paleobotanist, tracking the continent’s history of vegetation,” most recently Emeritus Professor of Botany at the University of Washington. (1) (edited with life data)

Aldo Leopold and Ernest Oberholtzer highly respected each other, and Ober has a book on Game Management signed by Leopold now shelved in upper Bird House.

Article written by Beth Waterhouse in March 2013, using:

(1) Aldo Leopold, A Fierce Green Fire (1996) by Marybeth Lorbecki

(2) Driven Wild (2002) by Paul Sutter

(3) Wilderness Forever: Howard Zahniser and the Path to the Wilderness Act

(2005) by Mark Harvey.

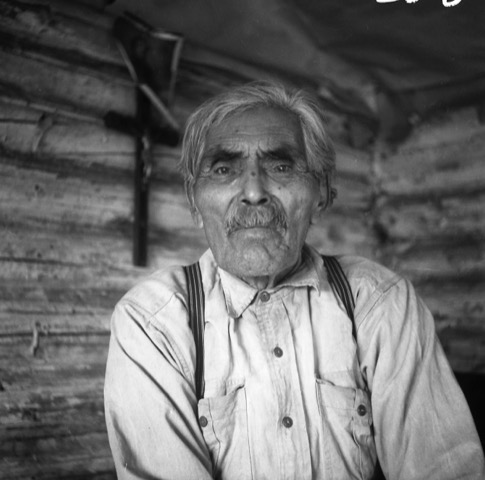

Billy Magee (Tay-tah-pah-swe-wi-tang)

Ober held a deep lifelong respect for this very quiet Ojibwe man. “Of all the Indians I have known in my life, with the single exception of his older sister, Billy was the most wonderful.”

Billy Magee was an Ojibwe trapper and guide who had a reputation for being so skilled he could follow a disused, overgrown Indian trail through the forest by feeling it beneath his feet. Ober first met Billy, then in his late 40s, in 1909, when Ober hired him as one of six Indian guides to accompany him during his “3,000-mile summer” of canoeing. In reference to one of their trips, Ober recalled telling his guide and companion,“Now Billy, I want to see everything. I don’t care how hard it is,” and according to Ober, “we went into places through which I could never have found my way.”

On June 26, 1912, Ober and Billy set out at the end of the railroad line at Le Pas, Manitoba, heading “toward magnetic north” on a 2,000-mile, four-month journey to Hudson Bay to explore the Canadian Barrens, an unmapped territory that hadn’t been visited by a white man since Samuel Hearne traveled through the area in 1770. It was the most ambitious and challenging of their many canoe trips together.

In the 1930s Ober opened an account with Mine Centre trader Edgar Bliss, known to the Indians as “Iceman,” to provide assistance to Billy and his family. When Billy died on May 1, 1938, Edgar wrote to Ober, “Billy was buried opposite the Headlight Portage. I gave them a nice flag to hang up along side of Grave.”

Gene Ritchie Monahan

Gene Monahan was a visual artist. After Ober’s death in 1977, she and her husband George served as unofficial caretakers of Mallard Island, and they devoted many long hours to organizing Ober’s papers. By the late 1980s, some 54,000 letters and reports were turned over to the Minnesota Historical Society.

Genevieve “Gene” Ritchie Monahan (1908 to 1994) lived every decade of the 20th Century and painted portraits in most of them. Gene was born and raised in Duluth, MN, schooled in Minneapolis and ran an art program in Faribault during WW II. Then it was off to Alaska, along with her Army husband and three children. By 1953, she had landed in the high art world of Greenwich Village in New York City.

However, Gene Monahan’s longest stay and true home was the tiny town of Ranier, MN. She first visited there in 1931, courting George Monahan whose parents were both doctors in International Falls, and thirty years later they returned and moved into a house at Main and Oak Streets, Ranier. Sadly, George died of cancer in 1965, but Gene Ritchie spent her remaining years based in Ranier and painting, sketching, and doing portraits as well as teaching all over the north country.

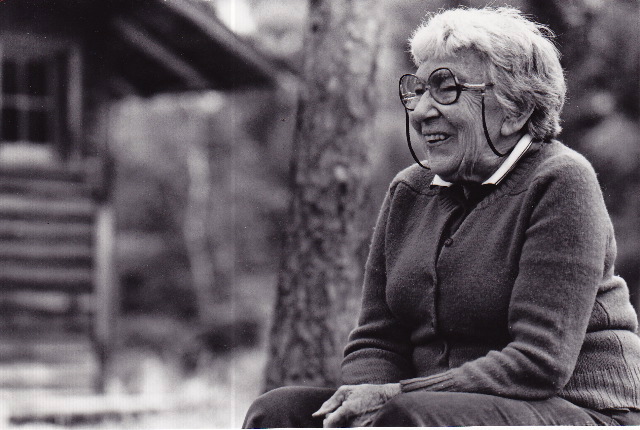

The reason Gene Ritchie Monahan is in Ober’s Address Book is that she was a good friend to Ober and one of the heirs to property at his death, and in fact served as volunteer “staff” on Mallard Island as it first began to see visitors in the 1980s. Gene took hold of the written materials archives and worked for years gathering, carrying, sorting, discarding chaff, and matching up correspondence. She corresponded with Ober’s friends, helped folks get out to the island, and even created her own artist’s studio out on Mallard (later renovated as the Artists’ Room.). Writes her son, Robin, (2011) “Gene was a gracious host to everyone who stopped by the Mallard. The coffee pot was always hot and a plate of cookies was served to all… Gene welcomed all as she had seen Ober do when he resided on the island.” Meanwhile, Gene Ritchie Monahan continued to paint and teach until she was into her eighties. Her work was exhibited nationally and internationally, including an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. (In this photo, Gene Ritchie sits near the fire ring in front of the tool shed become Library.)

Robert Hugh (and Marnee) Monahan

Written by: David F. Monahan (their son) My father, Robert

Hugh Monahan, Jr, was born in International Falls in 1914, the third child of Robert Hugh Monahan and Elizabeth Stevens Monahan, both pioneer medical doctors who established the first hospital in the area. He, too, became a doctor. While in medical school he met a nurse named Marian Louise Willey, and soon they decided on marriage. My father was excited to introduce his fiancé to his family, which logically included Ernest Oberholtzer (!) and they ventured to International Falls for a formal announcement. Mother once told me about her confusion over our father’s choice for his “Best Man,” as she thought that the man was a bit older than she expected. The best man in our parents wedding was Ernest Carl Oberholtzer. Ober was the age of our grandparents’ generation; however, our father was very close to him. We have come to the conclusion that our father didn’t have a very close relationship with his own father, and Ober was more of a father and friend than his own. It didn’t take any time for our mother to realize Ober’s charms. Robert and Marian were married on June 23, 1939 in Minneapolis. They spent their honeymoon on Ober’s Island in the peace and tranquility of the Japanese Cabin at the west end of The Mallard.

After WW II, we settled in St. Paul, Minnesota and spent our summers on Rainy Lake. On Memorial Day Weekends we would pack the family car with pets and move into our rustic cabin at Birch Point. Our family and various animals would stay until Labor Day, and our father would commute back and forth so he could keep his medical practice active. That first summer day on Rainy Lake would be consumed by preparation and getting launched. My early recollection was of a wooden boat with a whopping 9-HP Johnson motor that propelled us at a walking pace. By afternoon we would be east-bound in the channel between Deer Island and Jackfish Island. As we rounded the corner around The Crow, and The Mallard would come into view, it was magic. There would be Ober on the dock waving a greeting to us. It was absolutely amazing to a young boy that Ober knew that we were coming, because there was no telephone or electrical power. My brother and I would quickly be out of the boat and exploring every inch of the island. Of course, Ober would insist that we stay for dinner and spend the night. After dinner Ober would send us boys to the ice house where we would paw through wood shavings in search of a block of ice. Ober loved ice cream. We had to churn the cream by hand, and it was always a great show.

Sleeping on the island was an adventure. Many nights I fell asleep to the haunting rhythm of drums coming from the west end of the Hawk. Ober provided a camping site for the Indians from the Wild Potato Reservation on the Canadian side of the lake. This campsite was ideal to facilitate canoe travel from the reservation to Ranier, International Falls and Fort Frances; it was well used. After Ober became incapacitated, a caretaker was hired to oversee the islands. Part of this tragic turn of events was that, a short time later, I believe that the Indians were told they could no longer camp on that campsite. Things were already changing prior to Ober’s death.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, I overheard many long discussions between my father and other men about estate planning. Ober was a horribly impractical man, and he certainly dragged his feet dealing with the issue, but through our father’s encouragement the concept of the Oberholtzer Foundation was officially documented in his will. Ober chose the First National Bank in Minneapolis as executor of his estate. After Ober’s death in 1977, our father invited a group of Ober’s friends to re-activate the Oberholtzer Foundation. There were countless planning meetings at our cabin on Rainy Lake, and our mother took great delight in hosting the seemingly endless parade of interested parties.

Ober had no close family, and he had named thirteen heirs to his estate. This presented a huge problem for The First National Bank. Satisfying all these people with varying interests made the act of distribution of his assets a nightmare. The easy solution for the bank was to liquidate all the assets and distribute the funds to the thirteen named heirs, however, my father and others sincerely believed this was specifically contrary to Ober’s will. The bank had no concept of what Ober or his islands were all about. The individual assigned to the task of distributing the estate had never been in Koochiching County and certainly not out on a remote island. In fact, the bank was told that the islands were overgrown and the buildings were in a desperate state of decay, a condition that probably was grossly exaggerated. The bank was also told that there was a private party waiting to purchase everything in the current rundown condition. The bank summarily proceeded to consummate a sale.

In response, our father filed a lawsuit against the First National Bank to block the sale of the islands to a private party since several friends felt it was contrary to the specific wishes dictated in Ober’s will. The sale of the islands was successfully blocked. Our father wisely then invited the bank representative to serve on the board of this newly re-formed Oberholtzer Foundation. Through a complex combination of transactions, enough funds were raised to secure the islands for the immediate future. My parents worked countless hours and days with other friends of Oberholtzer to ensure that those ideas Ober had were fulfilled to the best of their abilities.

From a March 21, 1978 Letter from this group of friends: “We are named not as heirs to divide his estate in the conventional manner, but as stewards to continue his (Ober’s) own stewardship of a philosophy aimed at awakening his fellow man to the sheer joy of being, and being here, on this planet.”

Our father was the first president of the Oberholtzer Foundation. Three years after Ober’s death, our father was forced to give that position up due to his own health issues. It was one of the most difficult things he had to do, knowing that his health was failing, because he knew that the fragile foundation needed a leader and direction. He died a few months later (in November 1980). As you recall from part one, our mother, Marnee, who was immersed in the foundation from day one, took a position on the board after our father’s death. She knew that our father clearly cared deeply for his life-long friend, mentor, and father figure.

These key preliminary actions taken by our parents and other close friends laid the groundwork for the Oberholtzer Foundation as it exists today. Had the islands been sold into private ownership, the Oberholtzer Foundation would be lacking the essential component that drives the Foundation today—the islands.

Mrs. Notaway

Billy Magee’s older sister. Her Anishinaabe name was Naadowe Odishkekamigoog.*

“Mrs. Notaway was one of the greatest women I ever knew in all my life. And when she told you a story, you would see all the things she was talking about vividly. She would make little wigwams and little canoes with her hands as she was talking. You’d see them coming together right there before your eyes”

–Ober

Name (*) per Nancy Jones.

In an oral history interview, conducted by Evan Hart and Lucile Kane in February 1964, Ober described Mrs. Notawey:

“She was the oldest sister of Billy Magee. They were this marvelous old family. She was as talented as Sarah Bernhardt. She had long arms something like Sarah Bernhardt. And when she told you a story, you would see all the things she was taking about vividly. She would make little wigwams and little canoes with her hands as she was talking. You’d see them coming together right there before your eyes. And her voice wold change. It would go way down when she spoke in the voice of some of the men, and up again for the women. A wonderful quality, a rich voice.”

In 1948, Ober traveled to Mine Centre, where Mrs. Notaway lived with her cousin Johnny Whitefish. Ober wanted to interview Johnny about “all that he remembered that Billy had told him about our Hudson Bay trip.” Ober also wanted to record Mrs. Notaway to capture her wonderful, captivating voice on tape, but—never good at operating mechanical things—he failed to attach the microphone and missed his opportunity.

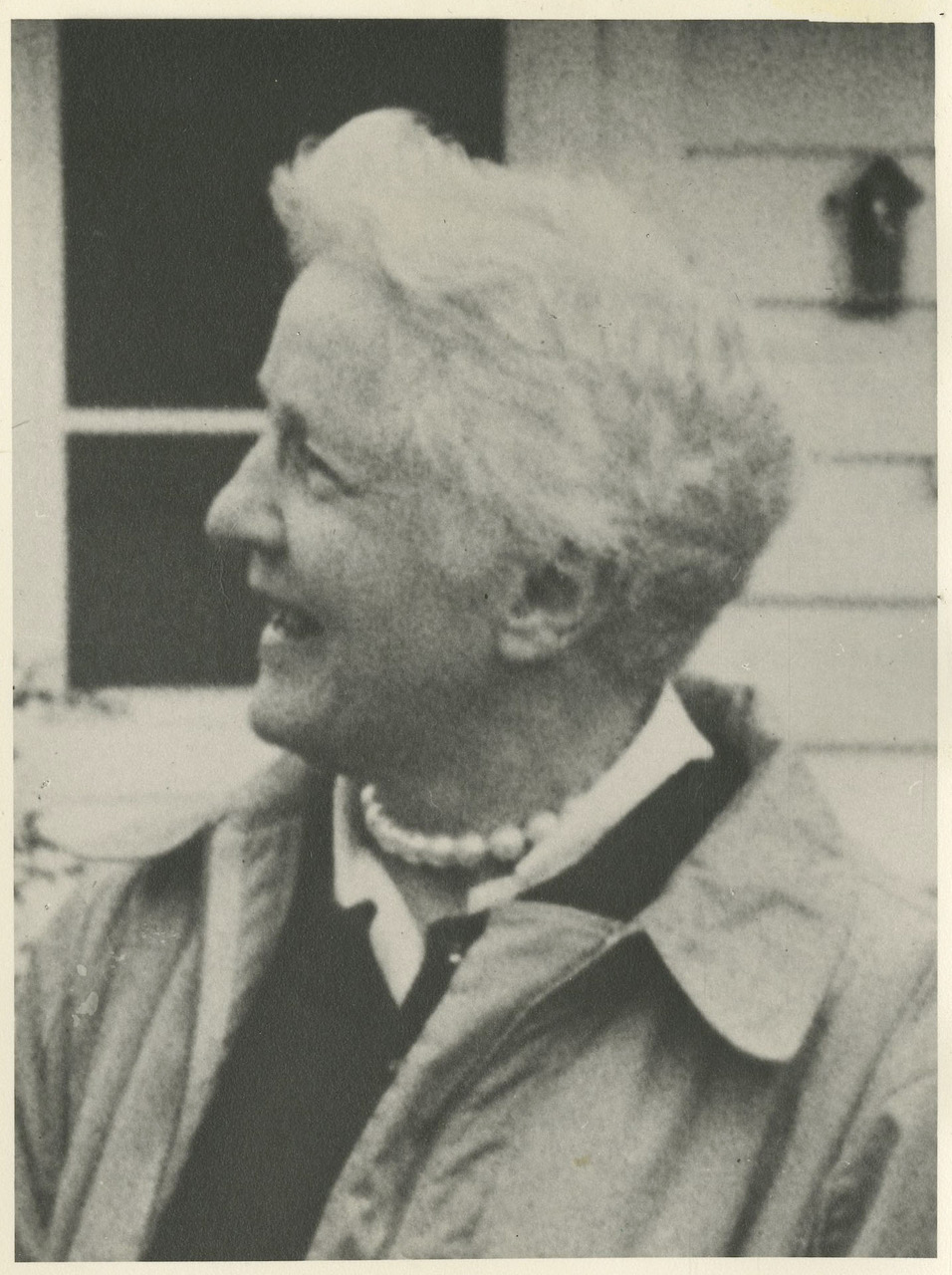

Rosa Carl Oberholtzer

“She’d never spent a night outdoors before. She sat bolt upright all night in the tent as lightning flashed in all directions. And she was imagining every moment that the tent, at least, was about to burn up, if she didn’t, or both of us. She was mostly concerned about me. She didn’t want to lose me. She’d always been devoted to me, but never an affectionate mother. But I knew that she thought I was worth preserving.”

–Ober

Rosa was a loving, protective mother who remained closely involved in Ober’s life until her death in 1929. Although never openly affectionate or demonstrative in expressing her love for her son, she offered him her unfailing support even when she didn’t fully approve of his decisions.

When Ober was 6 years old, Rosa filed for divorce from her husband Henry on the grounds of desertion. The next year, following the death of Ober’s younger brother Frank, she and Ober moved into the large and gracious home of her parents Ernest Carl and Sarah Marckley Carl on the corner of Sixth and Perry, Davenport.

In 1911, when Ober extended his European stay to serve as American vice consul at Hannover, Rosa sailed across the ocean to join him. Like her son, she suffered from a heart condition, and when she became ill on that trip Ober found a place for her to convalesce in southern England, where they spent the remainder of the winter.

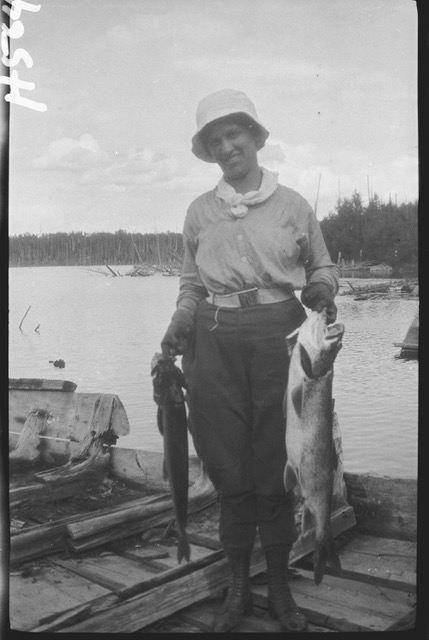

After Ober changed his permanent address to Ranier, Minnesota, in 1914, Rosa visited him for extended periods during the summer months. On her 1916 visit she came with the intention of inducing Ober to abandon his “northern nonsense” and come home to Davenport. Despite her misgivings about Ober’s decision to live on the edge of the northern wilderness, however, she worked side-by-side with him hauling topsoil, planting corn, and raising chickens, geese, turkeys, and sheep in his 1916–21 venture to develop Deer Island for agriculture and tourism.

On one occasion, Ober needed Rosa’s help with hauling some sheep to town. He wanted her to ride in the barge with the sheep “as a tranquilizer . . . so that they wouldn’t jump overboard.” Ober planned to tow the barge with a boat powered by a four-cylinder motor and with “about two hundred feet of rope connected to the barge behind.” As reported by Joe Paddock, Ober later told the story:

“The boat would stop every once in a while, and I’d have to kneel down to work on the engine. I finally got it going on about three cylinders, thinking I was lucky to have managed this. I was just congratulating myself on the fact that I had it all going, when I turned around and the barge was gone! I didn’t know where it had gone. I didn’t know. I was all alone. Working on the engine, I had drifted north with a south wind, you see, toward Canada, out among the islands. My mother was out there alone somewhere with all those sheep. She was somewhere on the other side of the Islands – just where I didn’t know. After a little exploring, I got around to the north side of the islands, and there I saw my mother standing at the front of the barge, waving at me.”

Although Rosa continued in poor health in 1924, she regularly cooked for as many as ten to fifteen people in the kitchen boat on Mallard Island, and she enjoyed providing piano accompaniment to Ober when he played the violin to entertain their guests. On August 14, 1929, after being an invalid for the past year and a half and suffering from pneumonia twice in the past year, she died, bequeathing Ober her house at 35 Oak Lane in Davenport and a commercial establishment at 422 West Second Street. Profit from the commercial property became Ober’s most stable source of income for the rest of his life.

Sigurd Olson

Sigurd F. Olson (1899 to 1982) died while snow-shoeing on a cold Ely winter day. Oberholtzer was fifteen years older than Sig and died in a nursing home after years of senility. Two such different endings, yet these two powerful men shared so much, including elements of their careers.

Sig Olson was at heart a writer and in the outer world, first a teacher and college dean. “Sometimes it can be hard to picture a successful writer as anything other than a successful writer,” wrote Sig’s son, Robert, decades after his father’s death. In the 1930s, Robert points to several journal entries by his father that showed how Sig’s writing served to keep him happy or as he said, “put him on his feet.” By 1938, when Sig wrote and published “Why Wilderness,” (American Forests magazine), he’d certainly found a clear message. Still, it took until 1956 for Sig’s first book, The Singing Wilderness, to be published by Alfred Knopf. Books then came in quick succession, to finally number nine. Listening Point (1958) was written about his new land on Burntside Lake, and on this writing continued until a title published in the year of his death. Sig was also a consultant with national parks for Secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall and noted volunteer president of the Wilderness Society.

Sig Olson carried an “organismic ethic,” says biographer David Backes (1977 The Life of Sigurd F. Olson: A Wilderness Within, U of Minn Press). Sig’s ethic told him that the biotic whole was greater than the sum of its parts. Nature does not lend itself to reductionary science. This developing ethic, much like Aldo Leopold’s, reversed Olson’s original view of predators (wolves). Like Leopold, he would model being the kind of man who could change his mind.

As Sig began to find his writer’s voice, the wilderness community also found him to be a great speaker. In as early as 1933, at an International Joint Commission hearing in Minneapolis, Sig spoke up about the power of wilderness and received applause. He began then, to consider a new career, away from the routine of the classroom.

People often ask how Sig became involved with the Quetico-Superior Council, the organization formed in opposition to the Backus-damming proposal and employing Ernest Oberholtzer. In short, it was a passing of the torch. More specifically, things shifted about the time of the dispute over the roadless area airplane rules and resort fly-in activity in the national forests.

After World War II, the number of planes and pilots in the US had increased, and the number of pilots wanting something to do that made sense in their lives increased in Minnesota. Post-war fly-in for wilderness fishing tripled. In 1944, there were nine fly-in resorts in the Quetico-Superior region; by 1946, just two years later, there were twenty. The Quetico-Superior Council took on this issue. And yet the group’s leadership differed on questions such as airplane activity. Also regarding logging: Ober said yes – he thought of the area in terms of zones of activity. Olson said no – saying it’s all about the aesthetic and the intangible value of whole forests.

Increasingly, meanwhile, Ernest Oberholtzer was spending more time on Mallard Island and while Ober held firm with his scope of 14,500 square miles for the Q-S region and its Program, Sig Olson, as he met with people in Canada, was beginning to compromise some. In 1946, F. B. Hubachek and Charles S. Kelly offered to raise money not just for Ober but also for Sig Olson, paying Sig to advocate and organize through the Izaak Walton League. By January 4, 1951, in a letter from Ober to Sig, we learn that their main disagreement was on this issue of the scope of the Quetico-Superior region. Ober still wanted to push for 15,000 square miles. Olson’s new treaty draft reflected the reality of about 3,000 square miles. Though they remained friends, things grew cool between the two men. In time, a friendship returned, and most certainly their mutual respect never wavered. Sig gave the eulogy at Ober’s funeral in 1977 entitling it, “A Defender of Wild Places.” “In truth,” says Joe Paddock, Ober’s biographer, “both men were legends.”

One can see how, in the late 1940s, Sig’s advocacy effort picked up as Ober’s waned. Ober was trying to reconnect with his Indian friends before Mrs. Notaway died. He was maintaining an island that now had several buildings and many guests. In 1950, Ober worked hard to help Frances Andrews buy Deer (Grassy) Island from William Hapgood, in Hapgood’s final years. In 1950, Mallard was badly flooded and many walls and all the gardens needed re-building; its ice was gone for that summer; its firewood had floated away. Also in 1950, Oberholtzer bought two more islands: Crow and Hawk, though he left them undeveloped. Clearly Ober’s Rainy Lake life was demanding more of him.

When Sigurd Olson was first published in 1956, Ober was trying to find the laborers to help him put the Frigate Friday houseboat up on land as his cabin on the mainland. Again his attention was needed at home, and it was natural that Oberholtzer’s energy for travel would lessen in his early seventies. It was also natural and a very good thing for the BWCAW effort that Sig Olson’s energy for this work was high, and that his voice was articulate on the beauty and value of the region. Sig resigned his deanship in 1947 to follow the career of writing and wilderness preservation. “I asked Sig what was his major victory,” said Herb Johnson in writing a 1980 piece on Olson. “He replied, ‘Carter’s signing the 1978 Act.’” A quote such as this shows us just how much of Sig’s focus in life was this wilderness advocacy work.

Sigurd Olson “was a sensitive and tender man,” wrote his son, “a man who felt things keenly and loved his world for its very self. He was a child of Nature…” The world remembers Sig Olson now with the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute out of Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin. His legacy and the Listening Point land on Burntside Lake is also protected through the work of the Listening Point Foundation, based in Ely, Minnesota.

Sig and Ober

Jackpot (Zhewe-Giizhig)

Zhewe-Giizhig was an Indigeous husband, father and grandfather, and he was also a pulpwood cutter as needed. “He would pull crews together and go across the lake to log the pulpwood, camping and often doing some gambling at night.” His grand-daughter, Nancy Potson Jones recalls, “Jackpot was the lucky one, and he’d often win the jackpots— sometimes they’d be playing for food. One day, he was not a part of the gambling group, and somebody asked, ‘Where’s Jackpot?’ And another said, ‘Didn’t you hear, they’ve just had a baby boy!’ And right then they laughed and said, “Ohhh Jackpot’s son!” And the name Jack Potson stuck as the English name for this boy. Jackpot’s wife’s name was Noodin-Aanakwadook.

Jack Potson

His Anishinaabe name was Giiwedinigwaneyaash. And his English name was given him in the story under “Jackpot” in this address book, or perhaps in another telling, such as the one quoted below. Jack Potson married Irene Banks. Dennis Jones (Pebaamibines) who has carried the Billy Magee family line all the way to the current board of trustees for Ober’s legacy, has this to say about naming and this, his family surname in particular:

Jack Potson and his wife, Irene.

Allan Snowball

“For 12 year old Allen Snowball, born with a seriously defective hip that kept him from walking, Ober found a Winnipeg surgeon and a financial donor, apparently Frances Andrews. As a result, Allen was able to walk almost normally through his adult years.”

–Joe Paddock

“Then I listened to Allen Snowball talk about Ober from a Native American perspective. Here was yet another Oberholtzer, friend and respectful student of aboriginal lifeways and spiritual practices, the man of spiritual power [who it seems took the medicine path himself].”

–Edith Rylander

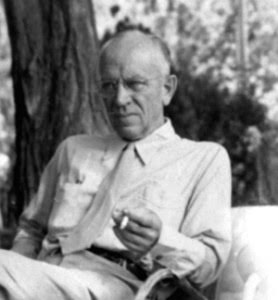

John Szarkowski

John Szarkowski has been called, “the most influential person in Twentieth Century photography.” He and Ernest Oberholtzer were friends.

Szarkowski created his own unique photographic statements of place and time, many of which are exhibited at the Pace/McGill Gallery in New York. He was also Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art from 1962 to 1991. Three months after Szarkowski’s death, The Guardian declared, “Everyone who cares about photography is in his debt.”

“When Szarkowski took over at Moma, there was not a single commercial gallery exhibiting photography in New York, and the form had still not been accepted by most curators or critics. Szarkowski changed all that.” [Guardian] At the Museum of Modern Art, Szarkowski hosted 160 exhibits including some very challenging shows, and he opened the doors to new and sometimes controversial work and photographers.

Szarkowski’s The Face of Minnesota (1958) was originally commissioned to commemorate the state’s centennial; it was then re-published for the sesquicentennial in 2008. U of M Press calls it “an eloquent tribute to the people and places of the North Star state.” See Barbara Breckenridge’s story for Mallard Island’s connection to this man and this book.

– Introduction by the Editor

An Interesting Visitor

by Barbara Ann Breckenridge

In the second week of September, 1955, I was completing three months as the summer cook on Mallard Island, cooking for Ober, Frances Andrews, and whoever else happened to be there. I heard that another guest was expected and, since it was my last week of cooking on the island, I was accustomed to various people showing up at any time; it just meant adding another place at the table. I wasn’t too surprised when a tall, thin young man appeared one afternoon. He commenced to pull a beautiful eggplant out of each jacket pocket, which was great except that I had no idea how to cook an eggplant. I had just turned 19 and was basically a meat and potatoes cook. Not wanting to display my ignorance, I thanked him for them and headed for the cookbooks. I found only one recipe, a fussy stuffed eggplant dish that took a lot of time and was not what Ober was expecting. But everyone graciously ate it without showing their disappointment that it wasn’t simply sliced and fried.

At dinner, our guest was introduced as John Szarkowski, a photographer. He was there to go on a canoe trip with Ober, who explained that they met on a train. In 1951 they were both traveling south from Minneapolis on the Rock Island Zephyr when they were asked to share a table in the dining car. Their conversation continued all evening and ended with Ober inviting Szarkowski to visit his island. This was a common occurrence for Ober—he never drove, usually traveled by train, and invited many casual acquaintances from trains to visit his island. He told me that sometimes people would show up years later saying he’d invited them and he would have no idea who they were. Being the gentleman he was, he always welcomed them as guests.

I didn’t see much of Szarkowski as he and Ober were busily planning the canoe trip. But in 1958 the University of Minnesota Press published a commemorative book about Minnesota for the state centennial. I realized when I saw the book that the photographs and text were by John Szarkowski, the young man I had met on Mallard Island. Several pictures were taken on Rainy Lake and even on Mallard Island, including one of my favorite pictures of Ober. I assume many of them were taken that fall of 1955.

Through the years, I have been alert for his name (certainly not a common one) and I’ve acquired several other books of his beautiful photography. Of course, John Szarkowski went on to a very distinguished career, teaching photography at several universities and serving as curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art. Through the years, I followed his career through newspaper articles, and I’ve collected some of his books. I enjoy his photography and descriptive text and find myself going back to his books frequently to look for particular pictures or descriptions.

Sewell Tyng

“He was really a wonderful character, a remarkable person, and I’d say he was the ablest fellow we ever dealt with during our Quetico-Superior struggles. He was on the edge of genius. . .”

–Ober

A New York lawyer from Harvard. A member of the “Deer Island Gang,” married to Ruth Hapgood, the daughter of the editor of Collier’s Magazine. His mother was a member of the Biltmore family, her second husband a Vanderbilt. In World War I, he served with the Red Cross ambulance group in France. At the Paris Peace Conference, he was Herbert Hoover’s private secretary.

There were many talented and dedicated people who worked closely with Ober in his decades-long effort to preserve wilderness. By all accounts, Sewell Tyng, a well-connected New York lawyer, was one of the more intelligent and energetic. In Keeper of the Wild, Joe Paddock offers the following description:

“Sometimes innocent, sometimes devious, Tyng was a large, nerdish-appearing man with thick glasses who experienced wide fluctuations in weight. His energy was immense and his genius considerable. He was an eastern blueblood, his mother a member of the Biltmore family, her second husband a Vanderbilt. In World War I, Tyng served with the Red Cross ambulance group in France, then as a second lieutenant in the Air Force. At the Paris Peace conference, he was Herbert Hoover’s private secretary. According to Ober, Tyng was as comfortable with woodsmen and Indians as with the financial and cultural elite . . .”

“With exceptional energy, intelligence, legal acuity, and an array of important contacts, Tyng would become a central support figure for Ober through the first two decades of the soon-to-emerge struggle to preserve a wilderness.”

An early example of Tyng’s usefulness to the movement was his role in coaching Ober when he attended the 1925 meeting of the International Joint Commission. The purpose of the meeting was to consider Edward Wellington Backus’s plan to use the Rainy Lake watershed as storage basins for industrial waterpower. Based on information Ober collected for him at that meeting, Tyng then drafted a legal brief opposing the Backus plan. After Ober had approved the arguments and had done some final editing, the brief was submitted to the Joint Commission, whose mood seemed to shift from giving the Backus plan routine approval to paying serious attention to the opposition.

In 1933, Tyng spent much of the year with Ober on Mallard Island following a romantic scandal and the breakup of his marriage to Ruth, who became mentally unstable and was committed to an institution. During his stay on the island, Tyng spent time writing a history of a World War I battle, later published to critical acclaim under the title Campaign of the Marne 1914. In the copy he gave to Ober he included a handwritten note: “To Ernest C. Oberholtzer, whose friendship in difficult days made this book possible.”

Johnnie Whitefish

Johnnie Whitefish was Billy Magee’s cousin. He lived near Mine Centre with Billy’s older sister, Mrs. Notaway. Long after Billy Magee’s death in 1938, Ober continued to maintain contact with Billy’s family.

In 1948, Ober traveled to interview Johnny about Billy’s memories of their 1912 canoe trip to Hudson Bay. The interview was conducted in Ojibwe and was tape-recorded. As Ober later recalled:

“And he (Johnnie) came the next two days and told me everything he possibly could, all that he remembered that Billy had told him about our Hudson Bay trip. He told me things I had forgotten and didn’t believe at first. It took me quite awhile before I was convinced that I had done what he said.”

Frederick S. Winston

By the 1920s, Frederick S. Winston (Sr.) was a young lawyer in Minneapolis who would both inspire and support Ernest Oberholtzer in the tenacious legal struggle to set aside all or most of the Quetico-Superior region, working with Ober for decades. Along with Charles Scott Kelly and Frank B. Hubachek, the three young lawyers held a strong vision— and Paddock calls them, “a remarkable trio.” (Keeper, pp 167+) This is Joe Paddock describing Winston: “Fred Winston was a tall and elegant, deeply respected man of liberal values from a wealthy family. The Winstons before him were engineers who had built the Great Northern Railroad and many of the government buildings in Mexico City. Fred worked as a public defender in Minneapolis, representing those who could not afford help. Like many young intellectuals of the period, was attracted to communism and the Russian experiment and would one day travel to Russia to study it close up. In support of Ober in the Quetico-Superior cause, he worked silently in the background, stepping into the light only when necessary. When the budget ran low, he often supported the project with his own or his family’s money, especially that of his mother. A man of Gandhiesque qualities, he gave himself to what he believed to be the greater good, always thought the best of his opponents, and was fearless in the midst of the angry confrontations that were to prove unsettling to the gentle Oberholtzer.” Paddock later clarifies, “clearly this group saw Ober as the authority, not only on the region, but on the Backus plan as well.” But it is just as clear in Paddock’s book as well as Newell R. Searle’s SAVING QUETICO SUPERIOR: A Land Set Apart, that the partnership went both ways. Searle re-tells the Leglslative battles prior to the Shipstead Nolan Act (1930) in great detail and gives a lot of credit and attention to the skills and bold steps taken by Fred Winston.

Howard Zahniser

Next year is the fiftieth anniversary of the passing of the Wilderness Act. Here, we feature a piece about its main author, Howard Zahniser (1906 to 1964).

“Howard Zahniser, or ‘Zahnie’ as he was known to friends and associates, grew up largely off the money economy and so did not get eye glasses until well into his youth. With their aid, he discovered that the world had sharper edges and even greater natural beauty than he had previously imagined. A public school teacher introduced him to bird-watching and inspired a lifelong fascination that no doubt attracted him to his eventual work in conservation.” – Edward Zahniser [1]

Howard Zahniser was born in February 1906 in Franklin, Pennsylvania. He spent his teenage years near the Allegheny National Forest. There, beginning with the birds, he developed a life-long interest in nature as well as a love of literature. He attended Greenville College in Illinois where he received a degree in humanities, later teaching school and working as a newspaper reporter. By 1930, Zahniser was employed by the USDA and other government agencies as a writer and an administrator. [2] His articles and essays caught the attention of leaders of the fledgling wilderness movement, and in 1945, he was hired to co-staff the Wilderness Society with Olaus Murie. Murie (in Wyoming) was policy director, and Zahniser was executive secretary of the organization in Washington, DC. Together they made a good pair, and both men were pivotal in the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. Zahnie’s spirit was alive in his bold writing:

“The need is for areas of the earth within which we stand without our mechanisms that make us masters over our environment—areas of wild nature in which we sense ourselves to be, what in fact I believe we are, dependent members of an interdependent community of living creatures that together derive their existence from the Sun.” – Howard Zahniser. [2]

By the time Zahniser was involved, the country had enjoyed a national park system for decades. Yet after the Model T and a resulting fast-paced influx of mankind into park spaces and beyond, advocates began to educate about “true wilderness.” And the country would need some standard of management across the country for these new areas. Such areas demanded federal law. As Zahniser penned that need, it was “for a positive program that will establish an enduring system of areas where we can be at peace and not forever feel that the wilderness is a battleground.” [2]

Although Howard Zahniser’s entre to the movement was as an administrator and writer, not as a wilderness hiker such as Bob Marshall or a canoeist like Ernest Oberholtzer, he took many trips into various wild places with all the greats. These were times of coalition building, yet they were also times of healing from the wounds of Washington, and Zahniser kept careful journals and took it all in. He began to coin the phrases that would stand the test of time in the Wilderness Act. “Untrammeled” (unfettered, unrestrained) was a good example of Zahnie’s word choice when describing wilderness, “an area where earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Other poignant phrases spoke of the human relationship to the wild: “The character of wilderness… embodies an attitude of humility and restraint that lifts our connection to a landscape from the utilitarian, commodity orientation… to the symbolic realm serving other human needs.”

In a very sad twist of history, by the time the Wilderness Society council met in Alaska in the summer of 1963, Olaus Murie was ill with cancer, and Zahniser was feeling the effects of his gradually weakening heart. [3] On the morning of May 4, 1964, Zahniser’s heart stopped in his sleep. He was only fifty-eight. The Wilderness Act, however, was then nearly completed—it was signed on September 3rd by President Lyndon Johnson. Alice Zahniser and Mardy Murie were both present at the signing ceremony. (Olaus had also died the previous October). The Wilderness Act of 1964 constitutes Howard Zahniser’s greatest professional legacy.

All along, Ernest Oberholtzer was in the background, supporting the work from his waning years on Mallard Island and his early years living in the Frigate Friday on the shore of Bancroft Bay. Their correspondence was going strong.

Today, Ed Zahniser and his older brother, Mathias Zahniser both recall a canoe trip taken with Ober in mid-July of 1956. Mathias shared his journal of that week, telling of fishing with Ober’s young friend, Bob Hilke. That trip had a rainy start in Orr, MN, and finished on Mallard. It was a lot of work for its young participants, but it left them changed.

In mid-April (of this year) Ed Zahniser shared clear memories of that particular trip, now over fifty years ago: “Ober let me sit in the bottom of his canoe when he ran a set of rapids that looked questionable. He stood up in the canoe, studying the rapids. I was 10 years old that summer; I hunkered down as instructed. It was a long rapids that I was glad not to have to hike around. He had stashed a lot of heavy gear in the canoe to save portaging it.

Ober was a magician with a reflector oven. I remember his baking a pineapple upside-down cake part way through the canoe trip– at an open wood fire. It furthered my education in how much outdoor cooking depended on what you knew about building and maintaining the right type of fire through the cooking process. What’s more, Ober could tell a complete, long story nonstop while cooking an entire backwoods meal.”